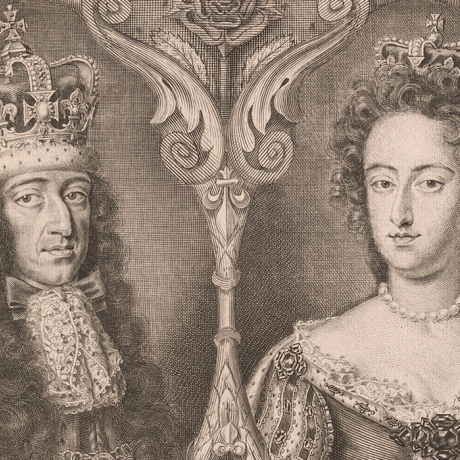

In 1689 Parliament declared that James had abdicated by deserting his kingdom. William (reigned 1689-1702) and Mary (reigned 1689-94) were offered the throne as joint monarchs.

They accepted a Declaration of Rights (later a Bill), drawn up by a Convention of Parliament, which limited the Sovereign's power, reaffirmed Parliament's claim to control taxation and legislation, and provided guarantees against the abuses of power which James II and the other Stuart Kings had committed.

The exclusion of James II and his heirs was extended to exclude all Roman Catholics from the throne, since 'it hath been found by experience that it is inconsistent with the safety and welfare of this protestant kingdom to be governed by a papist prince'. The Sovereign was required in his coronation oath to swear to maintain the Protestant religion.

The Bill was designed to ensure Parliament could function free from royal interference. The Sovereign was forbidden from suspending or dispensing with laws passed by Parliament, or imposing taxes without Parliamentary consent.

The Sovereign was not allowed to interfere with elections or freedom of speech, and proceedings in Parliament were not to be questioned in the courts or in any body outside Parliament itself. (This was the basis of modern parliamentary privilege.)

The Sovereign was required to summon Parliament frequently (the Triennial Act of 1694 reinforced this by requiring the regular summoning of Parliaments).

Parliament tightened control over the King's expenditure; the financial settlement reached with William and Mary deliberately made them dependent upon Parliament, as one Member of Parliament said, 'when princes have not needed money, they have not needed us'.

Finally, the King was forbidden to maintain a standing army in time of peace without Parliament's consent.

The Bill of Rights added further defences of individual rights. The King was forbidden to establish his own courts or to act as a judge himself, and the courts were forbidden to impose excessive bail or fines, or cruel and unusual punishments.

However, the Sovereign could still summon and dissolve Parliament, appoint and dismiss Ministers, veto legislation and declare war.

The so-called 'Glorious Revolution' has been much debated over the degree to which it was conservative or radical in character. The result was a permanent shift in power; although the monarchy remained of central importance, Parliament had become a permanent feature of political life.

The Toleration Act of 1689 gave all non-conformists except Roman Catholics freedom of worship, thus rewarding Protestant dissenters for their refusal to side with James II.

After 1688 there was a rapid development of party, as parliamentary sessions lengthened and the Triennial Act ensured frequent general elections.

Although the Tories had fully supported the Revolution, it was the Whigs (traditional critics of the monarchy) who supported William and consolidated their position.

Recognising the advisability of selecting a Ministry from the political party with the majority in the House of Commons, William appointed a Ministry in 1696 which was drawn from the Whigs.

Known as the Junto, it was regarded with suspicion by Members of Parliament as it met separately, but it may be regarded as the forerunner of the modern Cabinet of Ministers.

In 1697, Parliament decided to give an annual grant of £700,000 to the King for life, as a contribution to the expenses of civil government, which included judges' and ambassadors' salaries, as well as the Royal Household's expenses.

The Bill of Rights had established the succession with the heirs of Mary II, Anne and William III in that order, Mary had died of smallpox in 1694, aged 32, and without children. Anne's only surviving child (out of 17 children), The Duke of Gloucester, had died at the age of 11, and William was, in July 1700, dying. The succession had to be decided.

The Act of Settlement of 1701 was designed to secure the Protestant succession to the throne, and to strengthen the guarantees for ensuring parliamentary system of government. According to the Act, succession to the throne therefore went to Princess Sophia, Electress of Hanover, James VI & I's granddaughter, and her Protestant heirs.

The Act also laid down the conditions under which alone the Crown could be held. No Roman Catholic, nor anyone married to a Roman Catholic, could hold the English Crown. The Sovereign now had to swear to maintain the Church of England (and, after 1707, the Church of Scotland).

The Act of Settlement not only addressed the dynastic and religious aspects of succession, it also further restricted the powers and prerogatives of the Crown.

Under the Act, parliamentary consent had to be given for the Sovereign to engage in war or leave the country, and judges were to hold office on good conduct and not at royal pleasure - thus establishing judicial independence.

The Act of Settlement reinforced the Bill of Rights, in that it strengthened the principle that government was undertaken by the Sovereign and his or her constitutional advisers (i.e. his or her Ministers), not by the Sovereign and any personal advisers whom he or she happened to choose.

One of William's main reasons for accepting the throne was to reinforce the struggle against Louis XIV. William's foreign policy was dominated by the priority to contain French expansionism. England and the Dutch joined the coalition against France during the Nine Years' War, 1689-97.

Although Louis was forced to recognise William as King under the Treaty of Ryswick (1697), William's policy of intervention in Europe was costly in terms of finance and his popularity.

The Bank of England, established in 1694 to raise money for the war by borrowing, did not loosen the King's financial reliance on Parliament, as the national debt depended on parliamentary guarantees.

William's Dutch advisers were resented, and in 1699 his Dutch Blue Guards were forced to leave the country.

Never of robust health, William died as a result of complications from a fall whilst riding at Hampton Court in 1702, his sister-in-law, Anne, succeeded to the throne.