- Introduction

- Outbreak of the First World War

- Christmas 1914

- Edward, Prince of Wales

- Prince Albert

- Prince Alexander and Prince Maurice

- Princess Mary

- Visits to the Front

- The Home Front

- Royal Household Service Roll

- Scrolls and Plaques

- Armistice Day

- Unveiling the Cenotaph

- Returning troops

- The King's Pilgrimage 1922

Introduction

11 November 2018 marks 100 years since the end of the First World War.

The First World War was one of the deadliest conflicts in history – claiming the lives of nine million combatants. Seven million civilians also died as a direct result of the war.

To commemorate this important anniversary, every day until Remembrance Sunday we'll be sharing items from the Royal Archives that document how The Royal Family, and the Royal Household, played a part in the War.

The Royal Archives, housed in the Round Tower of Windsor Castle, preserves the personal and official correspondence of monarchs from George III (1760-1820) onwards, as well as administrative records of the departments of the Royal Household.

From diaries and personal letters to account books and speeches, the collections held by the Royal Archives record and reflect some of the most significant moments in British history and provide a fascinating insight into the life and work of past monarchs, their families, households and residences.

Outbreak of the First World War

By August 1914, the continental powers had declared war on each other; however it was still unclear whether Britain would enter into the conflict.

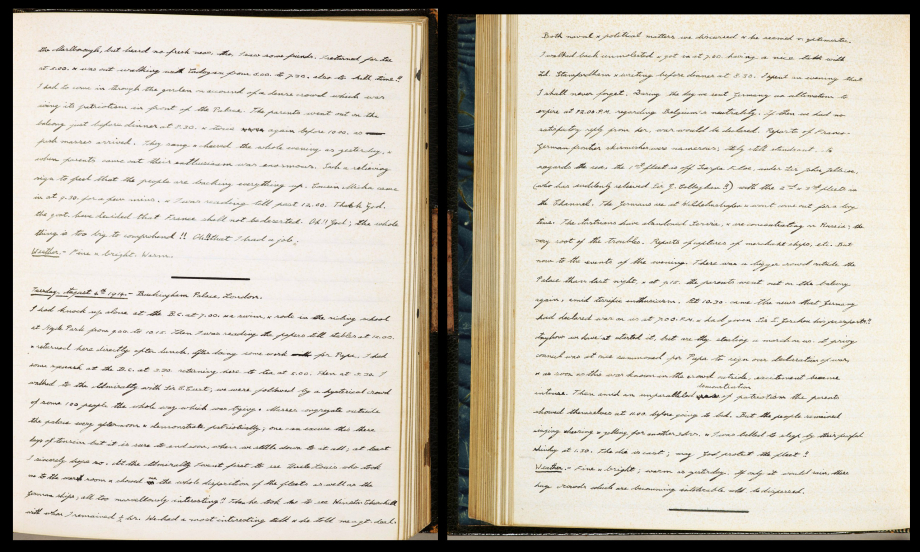

On 2 August, Queen Mary recorded her views on these uncertain times in her diary:

'A Large crowd assembled in front of the Palace & sang 'God save the King' and we went on the balcony & had a very good reception'.

These crowds would re-assemble on the day war was declared, about which she commented:

'It is too dreadful but we could not act otherwise'.

"…War news very bad. Germany has declared war on Russia – and will probably attack France… After dinner a large crowd assembled in front of the Palace & sang "God save the King" and we went on the balcony & had a very good reception. The Govt has not yet decided what our action is to be. A statement will be made in the House of Commons tomorrow after they have come to a decision."

On 4 August 1914, Britain declared war on Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and their allies.

King George V recorded in his diary the events leading up to and directly after the declaration of war. He describes when war was declared a large crowd assembled outside Buckingham Palace which 'was a never to be forgotten sight when May & I with David went on to the balcony, the cheering was terrific'.

"…Winston Churchill came to report at 1.0. that at the meeting of Cabinet this morning that we had sent [an] ultimatum to Germany that if by midnight tonight she did not give satisfactory answer about her troops passing through Belgium, [Sir William Edward] Goschen would ask for passports… At 10.30. the Prime Minister telephoned to say that Goschen had been given his passports at 7.0. this evening. I held a Council at 10.45.to declare war with Germany, it is a terrible catastrophe but it is not our fault. An enormous crowd collected outside the Palace, we went on the balcony both before & after dinner. When they heard that war had been declared the excitement increased & it was a never to be forgotten sight when May & I with David went on to the balcony, the cheering was terrific. Please God it may be soon over & that he will protect dear Bertie's life…"

On 4 August 1914, the day the First World War was declared, Edward, Prince of Wales, wrote this account of the day’s events in his diary:

"I spent an evening that I shall never forget. During the day we sent Germany an ultimatum to expire at 12.00.P.M. regarding Belgium’s neutrality. If then we had no satisfactory reply from her, war would be declared…There was a bigger crowd outside the Palace than last night, & at 9.15. the parents went out on the balcony again, amid terrific enthusiasm. At 10.30. came the news that Germany had declared war on us at 7.00 P.M…. A privy council was at once summoned for Papa to sign our declaration of war & as soon as this as known in the crowd outside, excitement became intense. Then amid an unparalleled demonstration of patriotism the parents showed themselves at 11.00. before going to bed…The die is cast; may God protect the fleet!!"

At the outbreak of War, Britain only had a small standing army, and relied on the strength of the Royal Navy to protect her interests.

This army was well-equipped and could be quickly deployed wherever needed. When war was declared this force was prepared for deployment in France. It is now more widely known as the British Expeditionary Force (BEF).

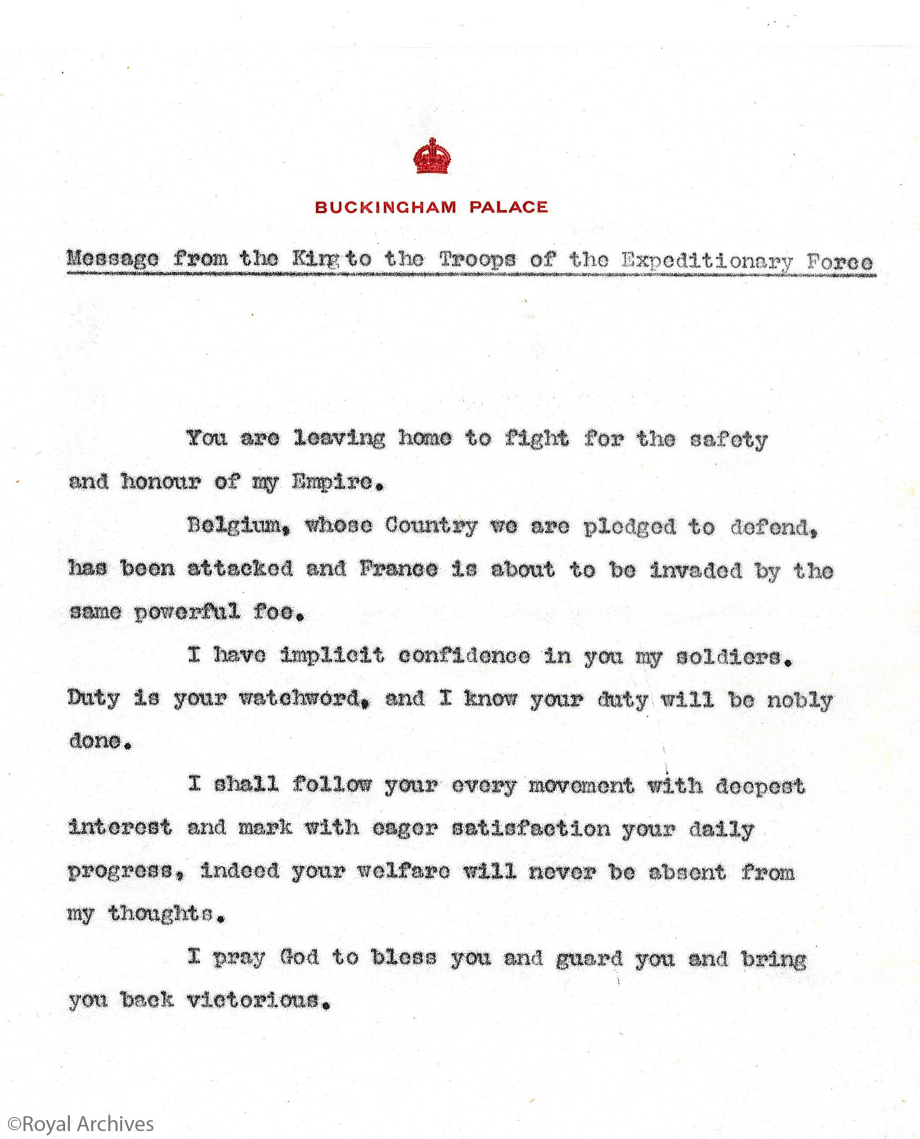

On 12 August 1914, prior to their departure for France, King George V sent a message to the Troops of the British Expeditionary Force. In this message the King expressed his 'implicit confidence in you my soldiers…I shall follow your every movement with deepest interest and mark with eager satisfaction your daily progress, indeed your welfare will never be absent from my thoughts.'

During the course of the war, as Head of State, King George V was kept informed of events by the Prime Minister and other members of the Government.

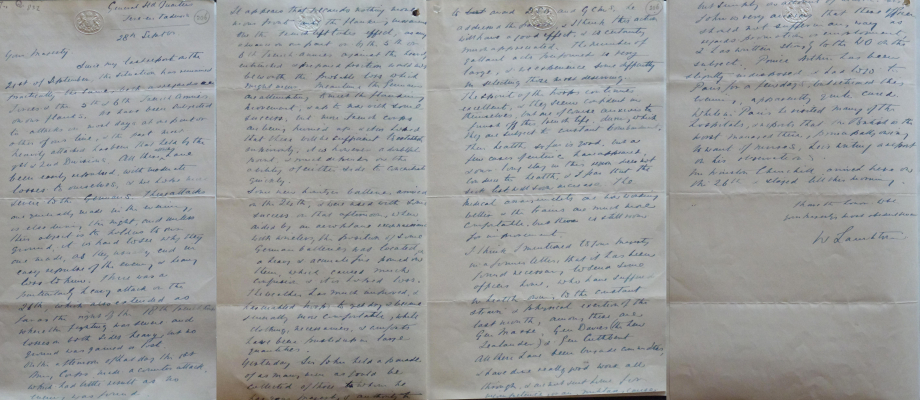

In addition, he requested that his Generals and Admirals "from time to time write to me quite freely & tell me how matters are progressing". During his role as Military Secretary to Commander-in-Chief in France, General William Lambton, wrote to the King every few weeks reporting events on the front line.

In this dispatch, dated 28 September 1914, Lambton reports that:

'The Spirit of the troops continues excellent, & they seem confident in themselves, but are of course anxious to finish off this Trench life, during which they are subject to constant bombardment.'

The full letter reads:

Your Majesty,

Since my last report on the 21st September, the situation has remained practically the same, both as regards our Forces & the 5th & 6th French Armies on our flanks. We have been subjected to attacks on most days at one part or other of our line, & the part most heavily attacked has been that held by the 1st & 2nd Divisions. All these attacks have been easily repulsed, with moderate losses to ourselves, & we hope more severe to the Germans. These attacks are generally made in the evening, or else during the night, and unless their object is to hold us to our ground, it is hard to see why they are made, as they usually end in easy repulse of the enemy & heavy loss to him. There was a particularly heavy attack on the 26th,which also extended as far as the right of the 18th French Corps where the fighting was severe and losses on both sides heavy but no ground was gained or lost.

…Some new howitzer batteries arrived on the 24th & were used with some success on that afternoon when aided by an aeroplane reconnaissance with wireless, the position of some German batteries was located & heavy & accurate fire poured on them, which caused much confusion & it is hoped loss. The weather has much improved, & has enabled troops to get dry & become generally more comfortable, while clothing, necessaries, & comforts have been pushed up in large quantities.

…The Spirit of the troops continues excellent, & they seem confident in themselves, but are of course anxious to finish off this Trench life, during which they are subject to constant bombardment. Their health so far is good, but a few cases of enteric have appeared, & our long stay in this region does not conduce to health, & I fear that the sick list will soon increase. The medical arrangements are now working better & the trains are much more comfortable, but there is still room of improvement.

…Mr Winston Churchill arrived here on the 26th & stayed till this morning.

Christmas 1914

Princess Mary Gift Box

On 14 October 1914, Princess Mary, daughter of King George V and Queen Mary, inaugurated the ‘Princess Mary’s Sailors’ and Soldiers’ Christmas Fund’ so that a Christmas gift could be sent to all at the Front. In November 1914, in response to many public requests, The Princess decided to extend the scheme greatly to include all men wearing The King's uniform on Christmas Day 1914. The present was an embossed brass box, which bore a profile of Princess Mary with the initial ‘M’ on either side, within a decorative border containing the names of the Allies at the beginning of the war and the words ‘Christmas 1914’.

The following items were stored inside:

- Smokers: packet of 20 cigarettes, tinder lighter or miscellaneous gift (tobacco pouch, shaving brush, comb, bullet pencil case, pencil case and packet of postcards, knife, scissors, cigarette case or purse), Christmas card, photograph of Princess Mary.

- Non-Smokers: packet of acid tablets/sweets, khaki writing case, Christmas card, photograph of Princess Mary.

The Christmas and New Year cards were printed in red lettering, with the Princess’s monogram and the date on the outside, and on the inside the message; "With best wishes for a Happy Christmas and a Victorious New Year from The Princess Mary and Friends at Home"

Over £160,000 raised, with surplus funds given to Queen Mary’s Maternity Home for the wives and infants of men the Armed Forces once the war was over.

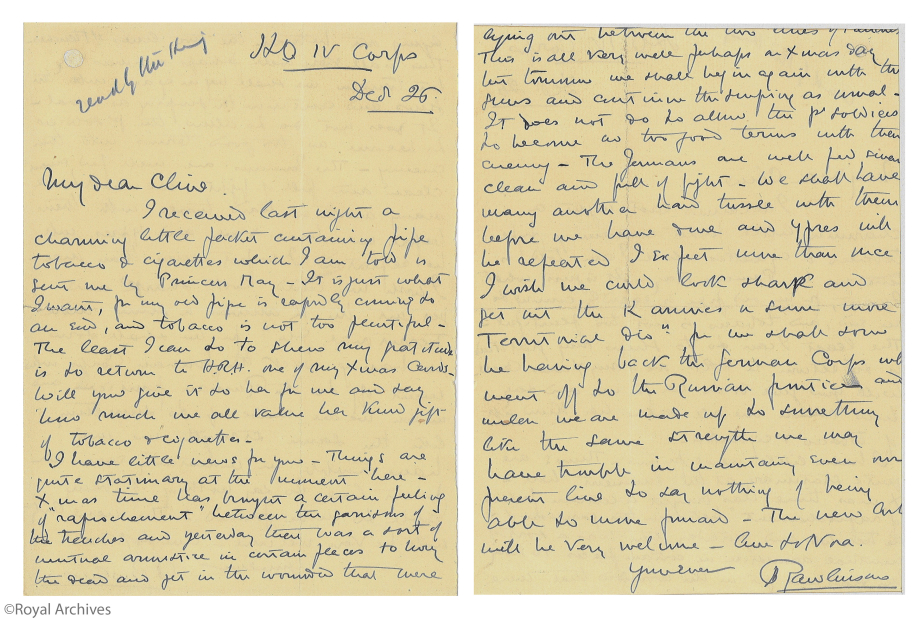

In this letter, dated 26 December 1914, Major General Sir Henry Rawlinson writes to Clive Wigram, Private Secretary to King George V, asking him to thank Princess Mary for the Gift Box, and "and say how much we all value her kind gift of tobacco & cigarettes".In discussing current events, he explains that "…Xmas time has brought a certain feeling of 'rapprochement' between the garrisons of the trenches and yesterday there was a sort of mutual armistice in certain places to bury the dead and get in the wounded that were lying out between the two lines of trenches. This is all very well perhaps on Xmas day but tomorrow we shall begin again with the guns and continue the sniping as usual…”

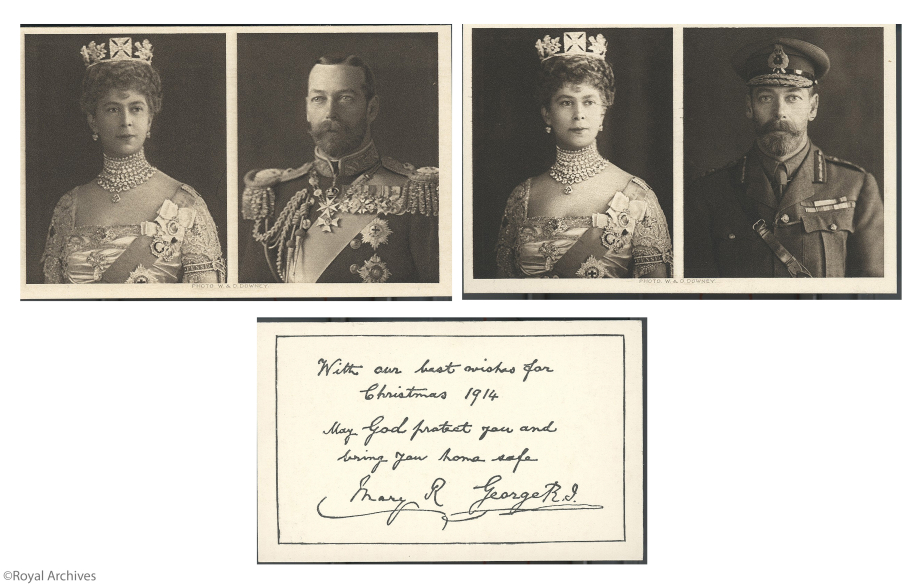

Christmas Cards

In 1914, at the suggestion of General Sir William Robertson, King George V and Queen Mary sent Christmas cards to members of the British (including Indian and Colonial) Armed Forces. The cards, in the form of postcards, bore photographs of the King and Queen on the front, and on the back a facsimile of a message written by The King and of his and The Queen's signatures.

Three versions were produced, one for the Army, for which the King was photographed in Khaki, one for the Navy, on which he is portrayed in Naval uniform, and another for the sick and wounded, using the same photographs as on the Army's card, but with a special message with good wishes for their recovery.

350,000 Army cards were produced for distribution to troops at the front in France and Belgium, 250,000 Navy cards for officers and men serving in ships flying the White Ensign or in hospital ships, and 60,000 cards for the sick and wounded in hospital on Christmas Day 1914 who had served afloat or at the front. No such cards were sent out at other Christmases during the war, because of the great increase in the number of those fighting.

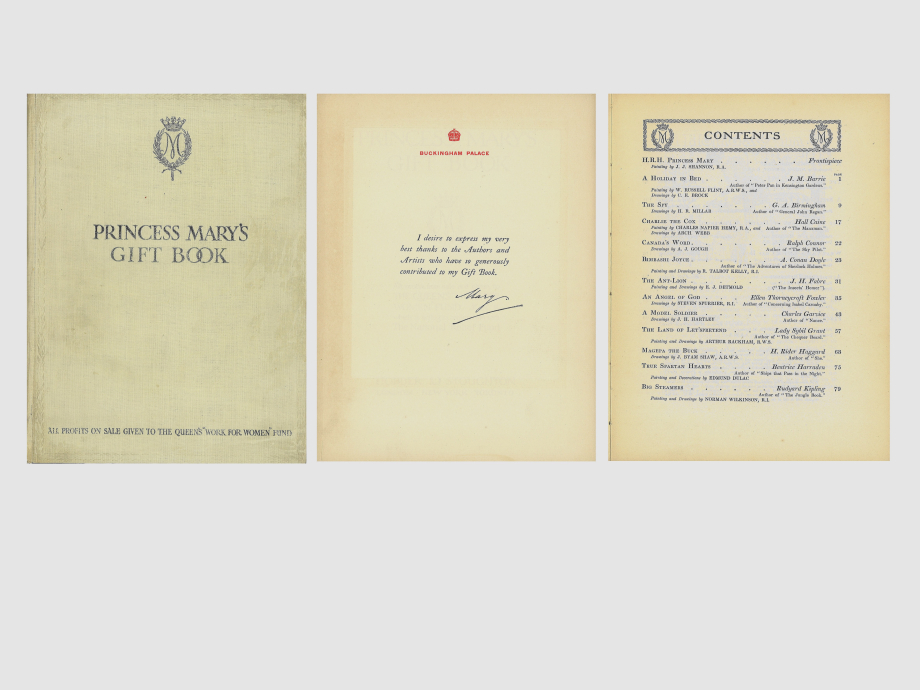

Princess Mary’s Christmas Book

On Christmas Day 1916 Queen Mary describes in her diary how herself and the King, along with Princess Mary, Prince George and Prince Henry, visited wounded soldiers at King George Hospital in London, during which they handed out copies of Princess Mary's Gift Book. This book was produced specifically to raise funds for the Queen's Work for Women Fund. This fund was launched in August 1914 at the instigation of Queen Mary, as a subsidiary of the National Relief Fund, to set up projects for employing women who were out of work as a result of the war. Princess Mary’s Gift Book is an anthology of stories and pictures by contemporary writers and artists, produced especially for this volume.

"Fine but dull. Service at 10, followed by the Communion Service. Busy sending cards & writing thanks. After luncheon we went to King George Hospital in Waterloo Rd & we & the children each took a floor & gave my "Gift book" to 1600 soldiers in the hospital. All the wards were decorated & looked very bright, & the men had some of their relations to tea afterwards. We were at the Hospital from 2.30 till 4.15…" - Princess Mary writing in her diary on Christmas Day 1916.

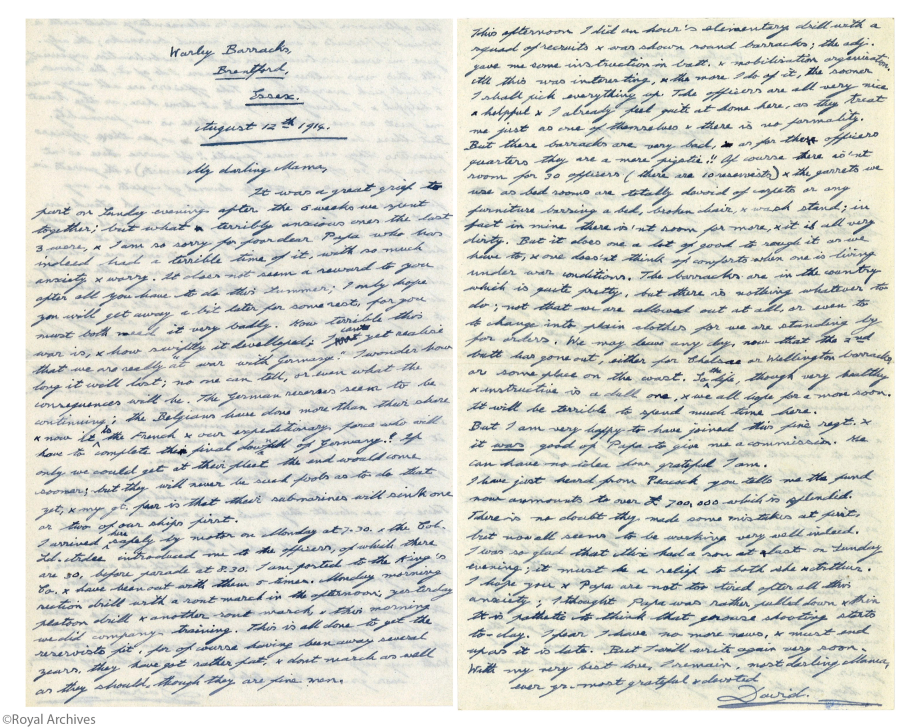

Edward, Prince of Wales

When War was declared on 4 August 1914, Edward, Prince of Wales (the future Edward VIII/Duke of Windsor) was desperate to serve his country on active service as soon as possible, but as heir to the throne, it was impossible to allow him to fight in France, where he could be wounded, captured by the enemy or killed. The Prince of Wales nevertheless begged his father, King George V, for a commission in the Grenadier Guards, which the King did grant. The Prince joined the 1st Battalion of the Grenadier Guards at Warley Barracks, Essex, on 11 August 1914.

Shortly after joining the 1st Battalion, Grenadier Guards, at their training barracks at Warley in mid-August 1914, The Prince of Wales, wrote to his mother, Queen Mary, describing his work, fellow soldiers and surroundings and also his happiness at being granted a commission. However, when the Battalion sailed for France on 8 September, The Prince was vastly disappointed to discover that he would not be accompanying it and would instead be staying in London with the 3rd Battalion, in line with his father’s wishes.

"…This afternoon I did an hour’s elementary drill with a squad of recruits & was shown round barracks; the adj. gave me some instruction in batt. & mobilisation organisation. All this was interesting, & the more I do of it, the sooner I shall pick everything up. The officers are all very nice & helpful & I already feel quite at home here, as they treat me just as one of themselves & there is no formality. But these barracks are very bad…it does one a lot of good to rough it as we have to, & one doesn’t think of comforts when one is living under war conditions…I am very happy to have joined this fine regt. & it was good of Papa to give me a commission. He can have no idea how grateful I am…"

The Prince’s anxiety to go to France led him to appeal to the Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, and eventually it was decided that The Prince would be posted to the General Headquarters of Field-Marshal Sir John French, Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force in France. He arrived at GHQ on 16 November 1914, where The Prince of Wales spent time in the various departments, such as lines of communication, rail transport and food supplies, in order to gain an insight into their respective activities.

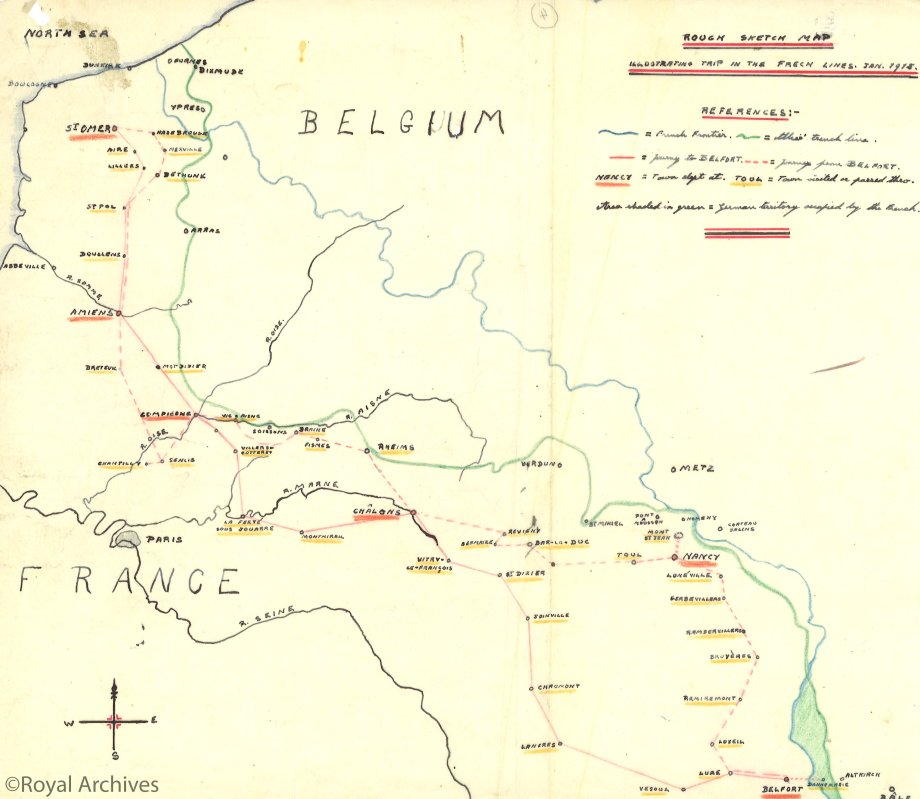

This map of the French lines, drawn by HRH in January 1915 was part of his time working for Field Marshal Sir John French.

The Prince surveyed the trenches used in the defensive line of St Venant-St Omer-Eperlecques in February 1915 and reconnoitred the whole length of the 30km of trenches on foot over the course of four and a half days.

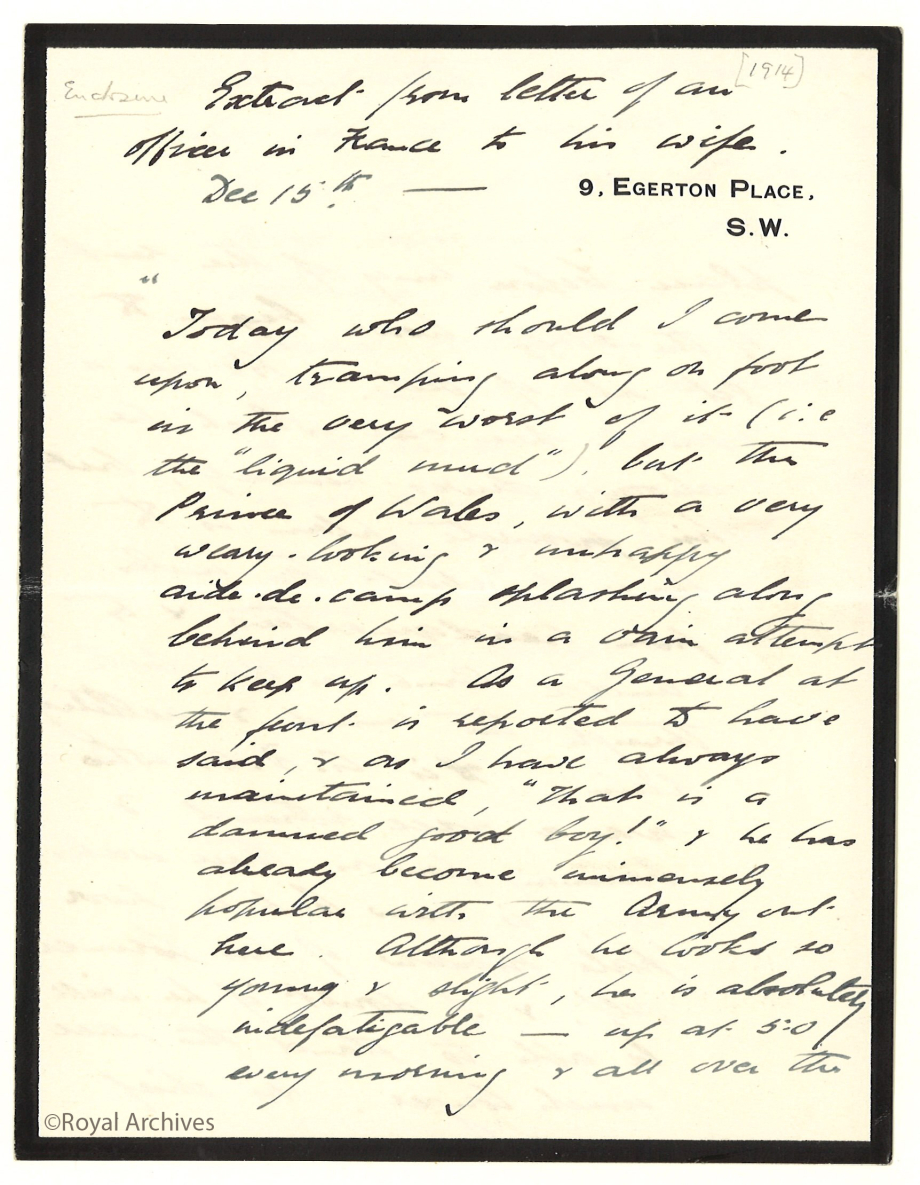

This extract from a letter from an officer in France to his wife, sent in December 1914, was forwarded by Austen Chamberlain to Lord Stamfordham, Private Secretary to King George V. The contents of the letter and the enthusiastic tone in which it was written, reflect the high esteem with which the Prince of Wales was regarded by the soldiers at the Front, and the morale-boosting effect his very presence in France had on the troops.

“Today who should I come upon, tramping along on front in the very worst of it (i.e. the “liquid mud”) but the Prince of Wales, with a very weary-looking & unhappy aide-de-camp splashing along behind him in a vain attempt to keep up. As a General at the front is reported to have said, & as I have always maintained, “That is a damned good boy!” & he has already become unanimously popular with the Army out here. Although he looks so young & slight, he is absolutely indefatigable – up at 5.0/ every morning & all over the place before any of the rest of the staff have begun to get out of bed. He has a small open car which he always drives himself, but his favourite plan is to leave it about ten miles from headquarters & to trudge home in the dark through the wind & pelting rain. His A.D.C. who was a nice rotund & beaming person three weeks ago, is now but a poor pale shadow of his former self, & I doubt if he will be able to stand the pace much longer. His chief preoccupation is to keep the boy out of danger &, as he is mad keen to share every experience of the soldiers like any last-joined subaltern, looking after him is by no means a sinecure I have not met him yet, but I see him very often & take much pleasure in his spirited goings on.”

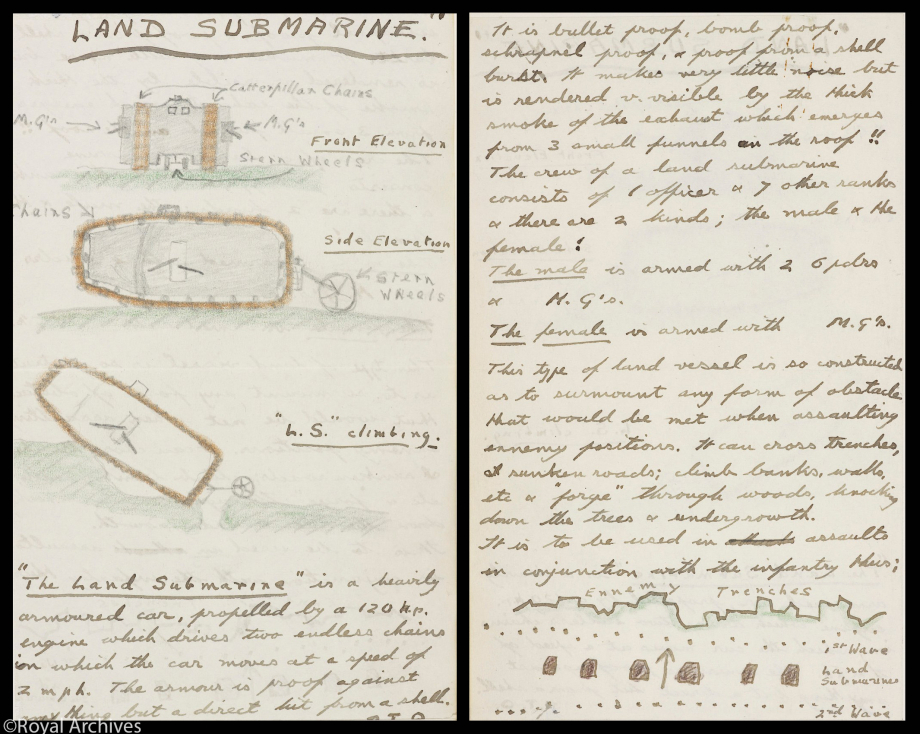

Below is a description by The Prince of Wales from his diary in September 1916 of a demonstration of ‘land submarines’ [tanks] which he saw when serving in the British Army in France, and sketches he drew of them for his father, King George V.

"…we motored via Amiens, St Vast, St Ouen & Domquer [Domqueur] to Yvrencheux to see these “Tanks” which is the code word for these new land submarines which are heavily armoured cars propelled by 120 H.P. engines which drive not wheels but those caterpillar chains to enable them to surmount any obstacle such as trenches[,] sunken rds etc[.] We left the car on the Yvrencheux – Oreux [Oneux] rd. & walked W. across fields to just S. of Gapennes where these “tanks” were operating with infantry, attacking!! …We wandered about watching these trials for about 2 hrs. & I went inside a “tank” at the end of which there are males & females; the males carry 2 6pdrs [pounders] & M.G’s & the females M.G’s!! They only do 2 m.p.h. but are silent. They are proof against schrapnell, bullets, bombs in fact any thing but a direct hit from a shell & each DIV. will have 6 to assault the trenches behind the 1st line of infantry & in front of the 2nd line!! They are good toys but I have’nt much faith in their success tho. their crews of 1 off. [officer] & 7 O.R. are d-d brave men!!..."

Prince Albert

Prince Albert, the future George VI, was the second son of King George V and Queen Mary. Known as Bertie, he enrolled in the Royal Naval College, first at Osborne and then Dartmouth. In September 1913 he was commissioned as a Midshipman on board HMS Collingwood, in which he was still serving at the outbreak of the First World War.

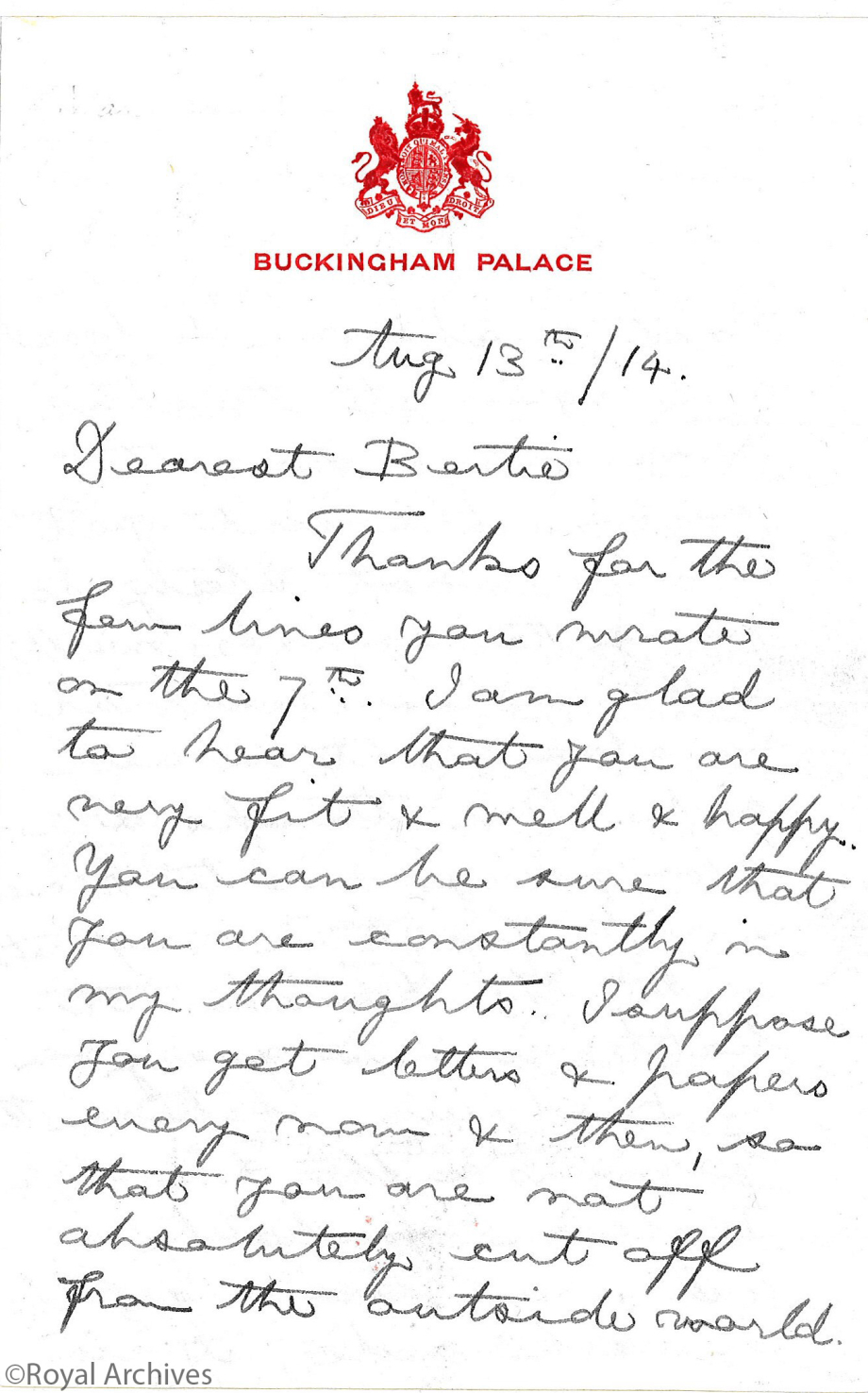

In this letter, dated 13 August 1914, King George V writes to Prince Albert keeping him updated on current events and informing him that "Our troops are now going over to France & will fight in cooperation with the French. A battle is now going on in Belgium between the Germans against the French & Belgians, probably a million men are engaged on each side, it is too awful to contemplate." He affectionately tells The Prince that "You can be sure that you are constantly in my thoughts".

Dearest Bertie,

Thanks for the few lines you wrote on the 7th. I am glad to hear that you are very fit & well & happy. You can be sure that you are constantly in my thoughts. I suppose you get letters & papers every now & then, so that you are not absolutely cut off from the outside world. Last night we declared war against Austria. France has done the same. We don't yet know what Italy is going to do, she will either remain neutral or else fight on our side. Our troops are now going over to France & will fight in cooperation with the French. A battle is now going on in Belgium between the Germans against the French & Belgians, probably a million men are engaged on each side, it is too awful to contemplate. The Germans have been checked by the Belgians at Liege which has given time for the French army to come up. The Russians are nearly ready to begin their advance on Germany. I hear Germany have strewn mines all over the place worse luck, to my mind that is a rather way of fighting, we have not laid one single one. Our weather has got very hot & I spend as much of my time as possible in the garden. I have a great deal to do & people to see all day. Mama & I on Tuesday went down to Aldershot to see all the troops before they started with the Expeditionary Force, they were loading very fit & in splendid spirits. I wonder what sort of weather you have been having. I suppose you are on ships provisions or do you have fresh meat & bread?

With love from Mama and Mary

God bless you my dear boy

Ever Yr very devoted Papa G.R.I

Battle of Jutland

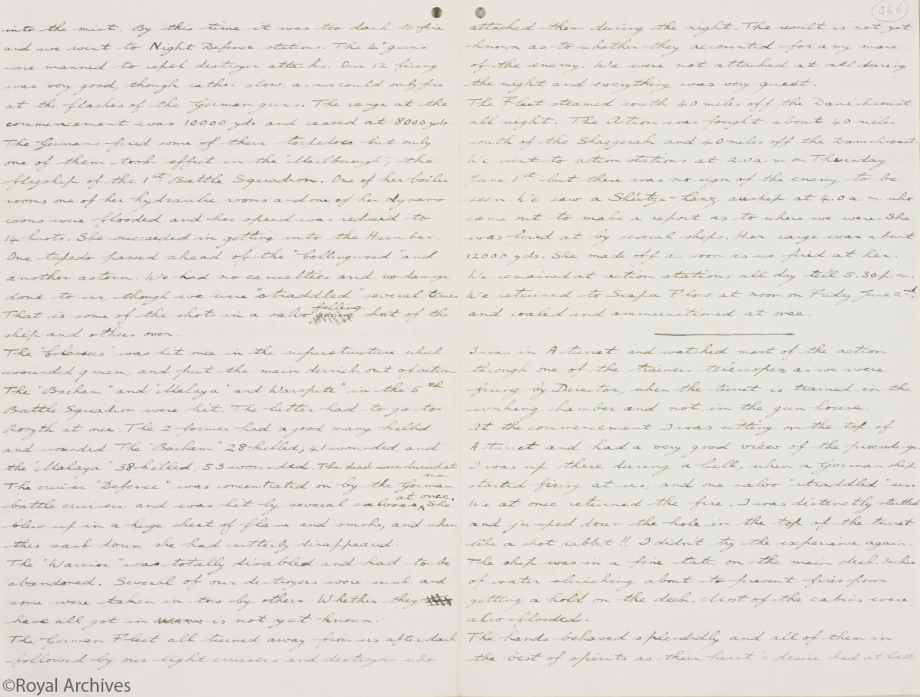

Account by Prince Albert of the Battle of Jutland, in which he served as a Sub-Lieutenant on board HMS Collingwood, and he remains the only British Sovereign to have seen action in battle since King William IV.

"…We went to “Action Stations” at 4.30 p.m. and saw the Battle Cruisers in action ahead of us on the starboard bow. Some of the other cruisers were firing on the port bow. As we came up the “Lion” leading our Battle Cruisers, appeared to be on fire the port side of the forecastle, but it was not serious. They turned up to starboard so as not to cut across the bows of the Fleet. As far as one could see only 2 German Battle Squadrons and all their Battle Cruisers were out. The “Colossus” leading the 6th division with the “Collingwood” her next astern were nearest the enemy. The whole Fleet deployed at 5.0 and opened out. We opened fire at 5.37 p.m. on some German light cruisers. The “Collingwoods”’s second salvo hit one of them which set her on fire, and sank after two more salvoes were fired into her…

I was in A turret and watched most of the action through one of the trainers telescopes, as we were firing by Director, when the turret is trained in the working chamber and not in the gun house. At the commencement I was sitting on the top of A turret and had a very good view of the proceedings. I was up there during a lull, when a German ship started firing at us, and one salvo “straddled” us. We at once returned the fire. I was distinctly startled and jumped down the hole in the top of the turret like a shot rabbit!! I didn’t try the experience again…2

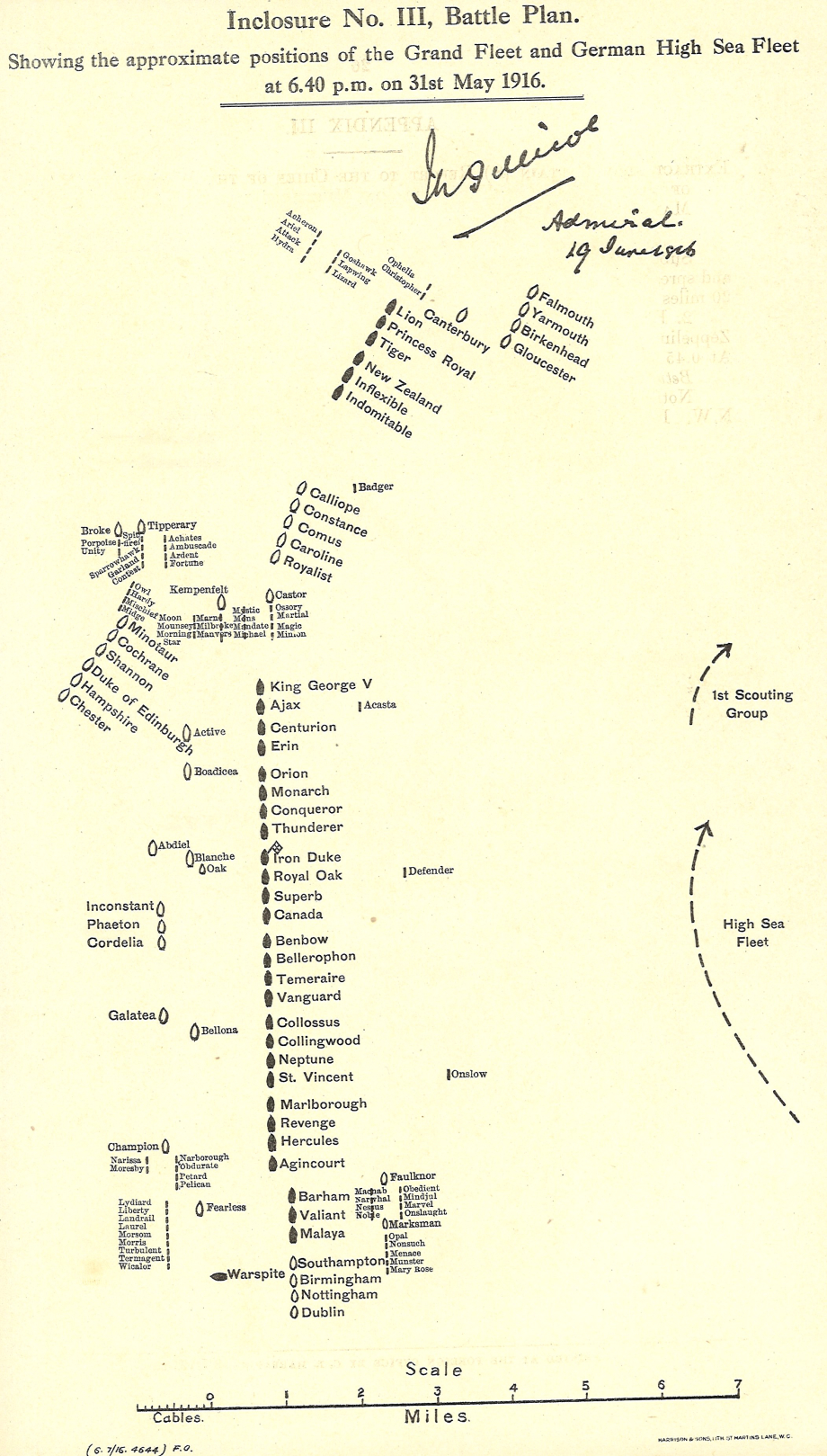

Battle Plan showing the approximate positions of the Grand Fleet and the German High Sea Fleet at 6:40pm on 31st Mary 1916, which has been signed by Admiral Jellicoe.

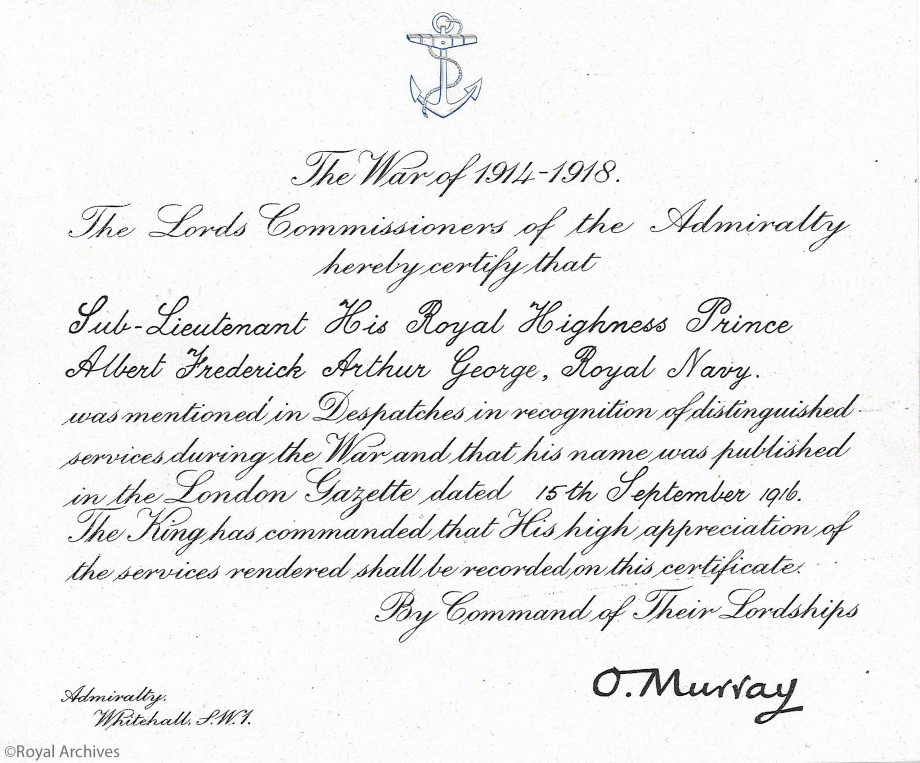

Certificate address to Prince Albert informing him that he had been mentioned in dispatches for his role in the Battle of Jutland, which had appeared in the London Gazette on 15 September 1916:

Royal Naval Air Service

In January 1918, Prince Albert transferred to the Royal Naval Air Service, and was posted to the RNAS Training Establishment at Cranwell , where he learnt to fly, becoming the first member of the royal family to hold a pilot’s licence. He wrote to his mother, Queen Mary, on 5th March 1918 about his first flight in an aeroplane explaining that "It was a curious sensation and one which takes a lot of getting used to. I did enjoy it on the whole, but I don't think I should like flying as a pastime. I would much sooner be on the ground!! It feels safer!!"

His main role whilst at RNAS Cranwell was as Officer Commanding No.4 Squadron, Boy Wing. He wrote to his father, King George V, explaining that "I am going to run them as an entirely separate unit to the remainder of the men…I shall have to punish them myself and grant their requests for leave etc." In April 1918, the Royal Naval Air Service merged with the Royal Flying Corps to form the Royal Air Force. A few months later, after a short training course, Prince Albert took command of No.5 RAF Cadet Wing. However, he still wished to see service in France and in October he was posted to the staff of General Hugh Trenchard, General Officer Commanding Independent Air Force [strategic bombing force of the Royal Air Force], at the R.A.F Headquarters at Autingy. Whilst there he witnessed both day and night operations undertaken, not only British, but American, French and Italian squadrons.

Photograph of Prince Albert in his flying outfit during his training at RNAS Cranwell.

Prince Alexander and Prince Maurice

Prince Alexander of Battenberg, eldest son of Princess Beatrice and Prince Henry of Battenberg, was born in 1886 at Windsor Castle. After some years in the Royal Navy, Prince Alexander, known as Drino, joined the British Army as a Second Lieutenant in the Grenadier Guards in 1911.

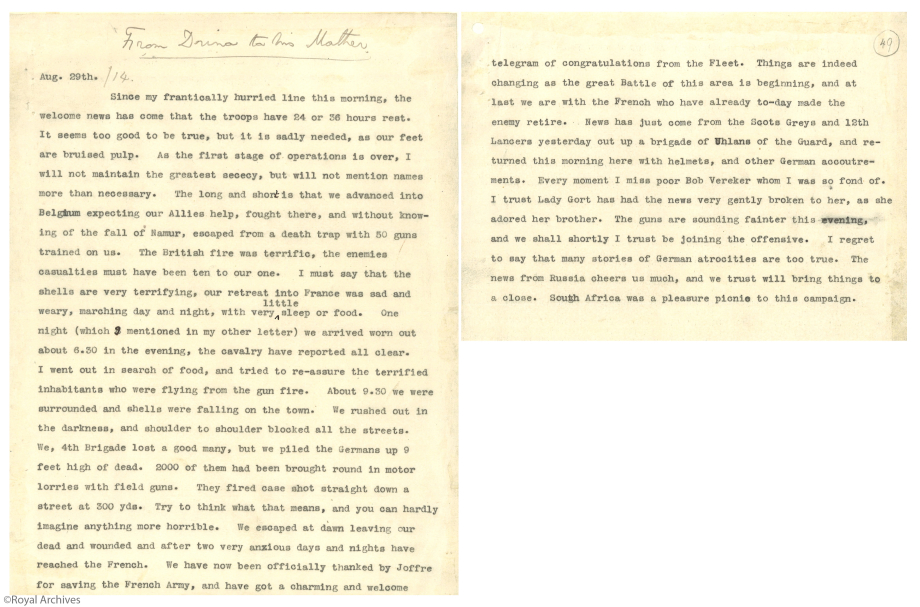

By the time of the outbreak of the First World War, Prince Alexander had been promoted to Lieutenant and was soon in France on active service. In this letter to his mother, dated 29 August 1914, Prince Alexander describes his first experiences of battle and the terrible loss of men. He closes the letter by stating that ‘South Africa [Boer War] was a pleasure picnic to this campaign’.

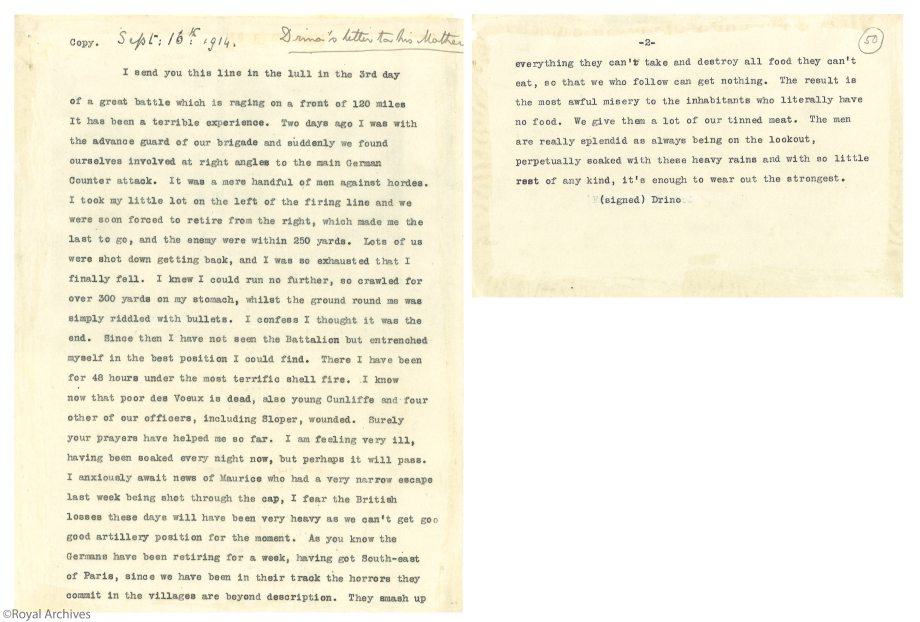

On 16 September 1914, Prince Alexander wrote again to Princess Beatrice during ‘lull in the 3rd day of a great battle which…has been a terrible experience’. His brigade had suddenly found themselves ‘involved at right angles to the main German Counter attack. It was a mere handful of men against hordes…Lots of us were shot down getting back, and I was so exhausted that I finally fell. I knew I could run no further, so crawled for over 300 yards on my stomach, whilst the ground round me was simply riddled with bullets. I confess I thought it was the end…’

Prince Alexander survived the First World War, having served with distinction throughout. In 1917, the Battenberg family took the surname Mountbatten. Prince Alexander became Sir Alexander Mountbatten and was created Marquess of Carisbrooke in 1930.

Prince Maurice of Battenberg was the youngest child of Princess Beatrice and Prince Henry of Battenberg, and the youngest grandchild of Queen Victoria. Born in 1891, the young Prince volunteered as a Lieutenant in the King’s Royal Rifle Corps in the First World War and was part of the British Expeditionary Force which arrived in France in August 1914.

In this letter to his mother, dated 16 September 1914, Prince Maurice describes the terrible conditions his company was facing in France and does not spare her the details of the shelling and bloodshed. He refers to his brother Alexander, known as Drino, who was also in France serving with the Grenadier Guards and had just been wounded.

On 18 October 1914, Prince Maurice wrote to his mother informing her he was safe at Hazebrouck in northern France, but was awaiting orders to move elsewhere for the next attack on the Germans.

Just a few days later, Prince Maurice was killed in action on 27 October during the First Battle of Ypres. He was 23 years old and was the only member of the British Royal Family to die in action during the First World War. The Times report of his death stated that Prince Maurice ‘was leading his company in an attack when he was struck by a shrapnel bullet from a bursting shell and died almost immediately’. At Princess Beatrice’s request, Prince Maurice was buried at Ypres Town Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemetery and a memorial to him was placed at the Royal Burial Ground at Frogmore, Windsor.

Princess Mary

Princess Mary was the only daughter of King George V and Queen Mary. Aged 17 at the outbreak of the First World War, Princess Mary visited hospitals and welfare organisations with her mother during the first years of the war, and became very involved with charities which provided assistance to the mothers, wives and children of soldiers serving in France.

She also worked in a canteen in a munitions factory in Hayes and was particularly interested in nursing, especially the work of the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD). This interest led to Princess Mary taking an advanced course in nursing, which she passed with honours. Much to her regret however, she was not allowed to serve in France.

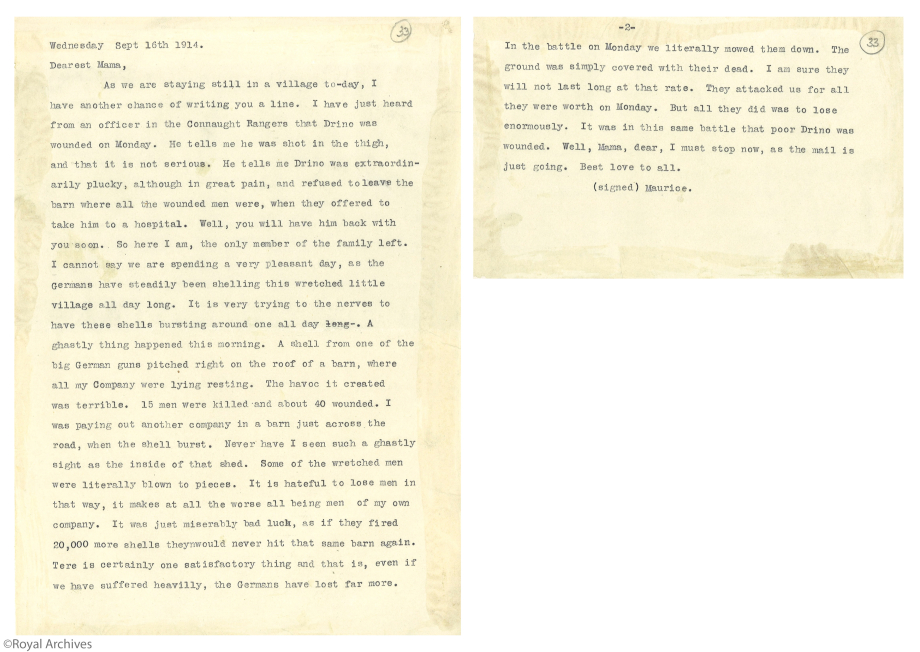

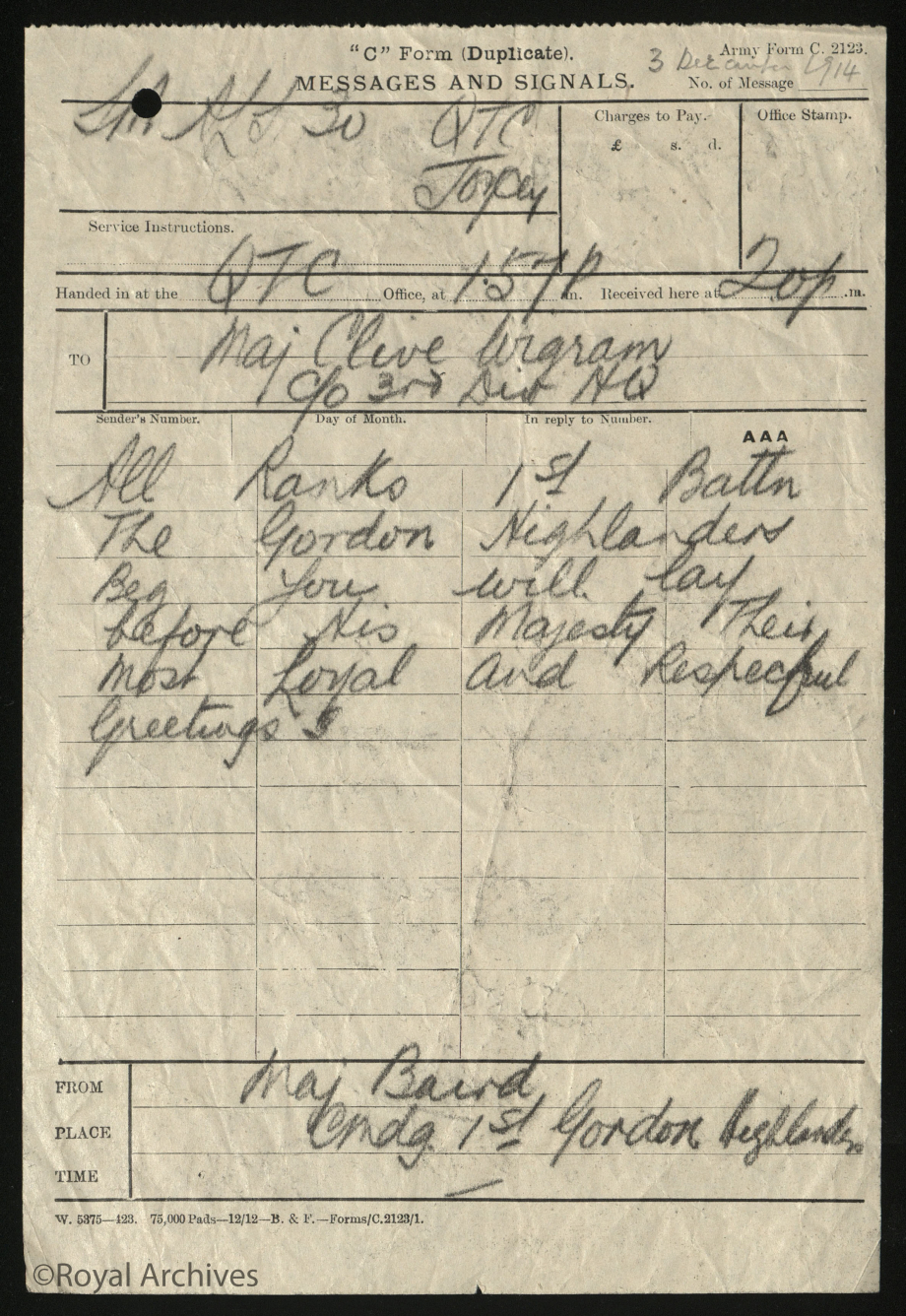

In 1918, at the age of 21, Princess Mary went to work as a VAD probationer at the Hospital for Sick Children in Great Ormond Street. The announcement, made in The Times on 26 June, stated that the Princess was to work in the Alexandra Ward two days each week. Queen Mary visited her daughter at the hospital and reported on Princess Mary’s work in a letter to her son, Prince Albert (later King George VI) on 10 August 1918:

‘…This morning I went to the Great Ormond St Hospital to see Mary working in her ward. Both the Dr & Matron are much pleased with her work which she does very nicely & thoroughly. She has nice light hands for the work and takes a great deal of trouble over the children’s cases. She dressed a wound of one child; removed a needle with saline out of a baby’s side, made small incisions on another child’s arm, a test to ascertain whether the child is tuberculous or not – of course to me who knows little or nothing of such things it was a great surprise to find my daughter doing all this in the quietest, most composed manner!’…

Princess Mary left the hospital and nursing, her true vocation, in 1920. On her departure she was made President of the hospital and in 1926, she became Commandant-in-Chief of British Red Cross detachments. Princess Mary married Henry, Viscount Lascelles, in 1922

Visits to the Front

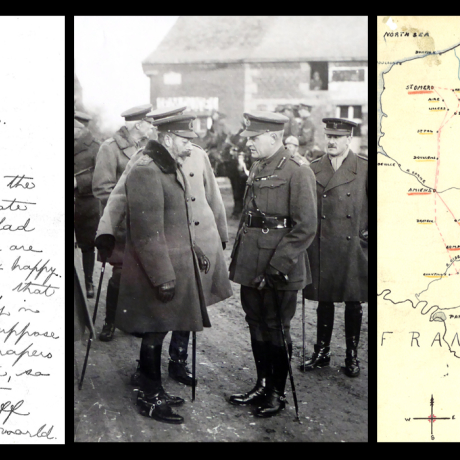

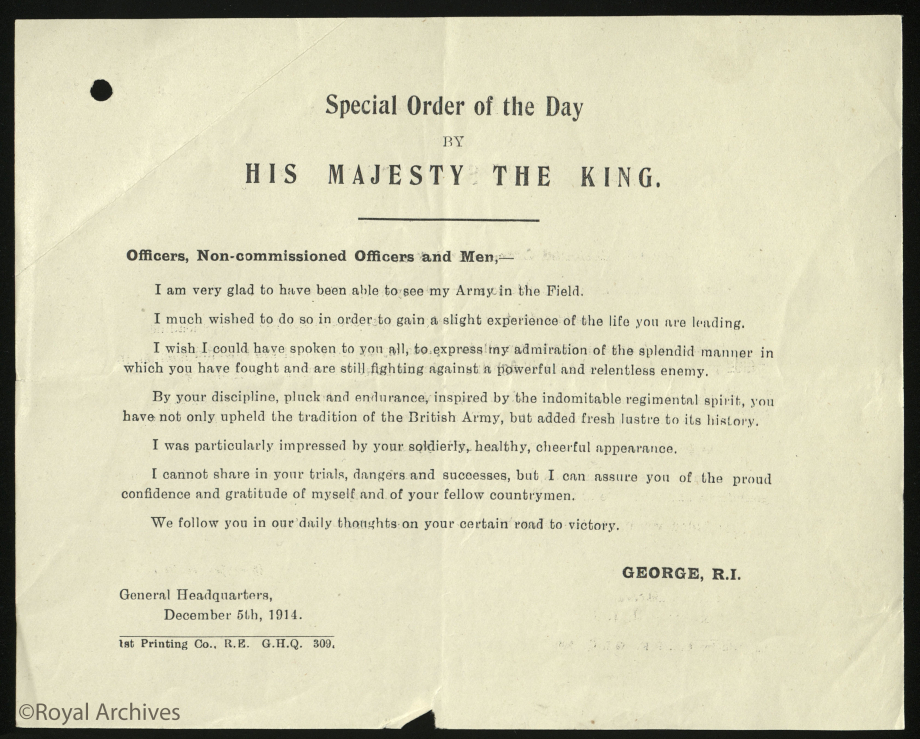

During the First World War, King George V undertook several visits to the Western Front to witness for himself the situation of his Armed Forces: 29 November – 5 December 1914, 21 October – 1 November 1915, 7 – 15 August 1916, 3 – 14 July 1917, 28 – 30 March 1918, 5 – 13 August 1918, 27 November – 10 December 1918.

On 8 July 1917, King George V and Field Marshal Sir Julian Byng visited the site of the Battle of the Somme.

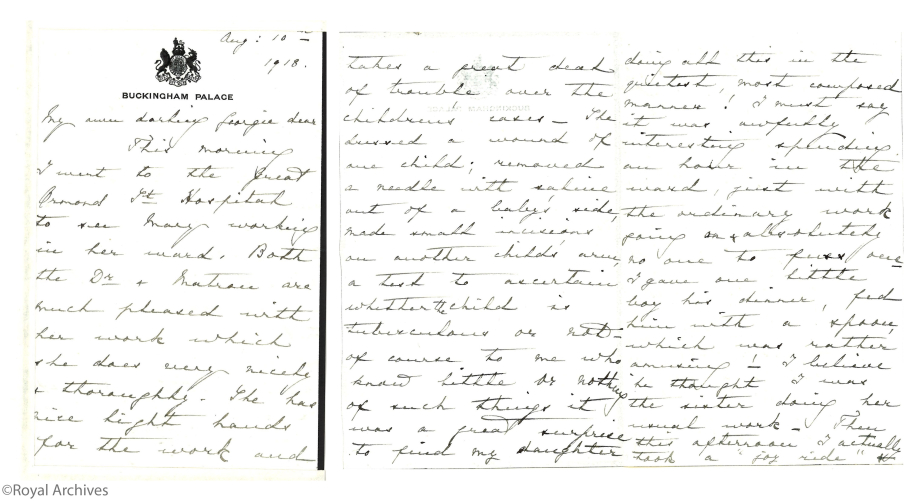

On the afternoon of the 3 December 1914, King George V visited the Headquarters of the 3rd Division of the British Army stationed at Scherpenberg Hill. He climbed to the top of this hill "…from where we got a splendid view of the battlefield, as it was a remarkably clear afternoon. We were only about three miles from the enemy's trenches. Ypres, Gheluvelt, Wytschaete, Messines & Mont Kemmel being easily seen with glasses…. While on the hill I received a message by telephone from Major Baird & Officers of the Gordon Highlanders in the trenches…I have now seen all the troops out here in the last three days except those actually in the trenches".

The message from Major Baird reads “All ranks 1st Battn The Gordon Highlanders beg you will lay before His Majesty their most loyal and respectful greetings”

On the last day of his visit the King sent the above message, via a Special Order of the Day, to all the British and Commonwealth Forces.

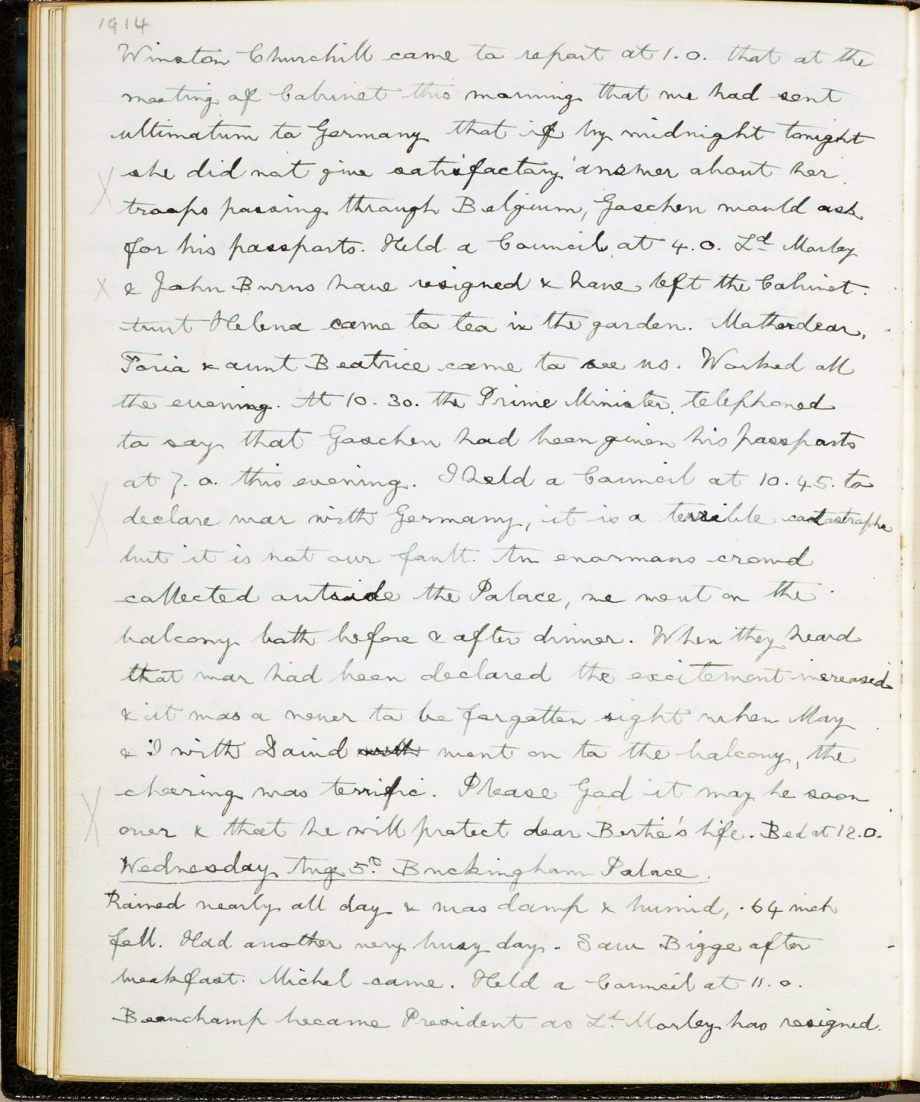

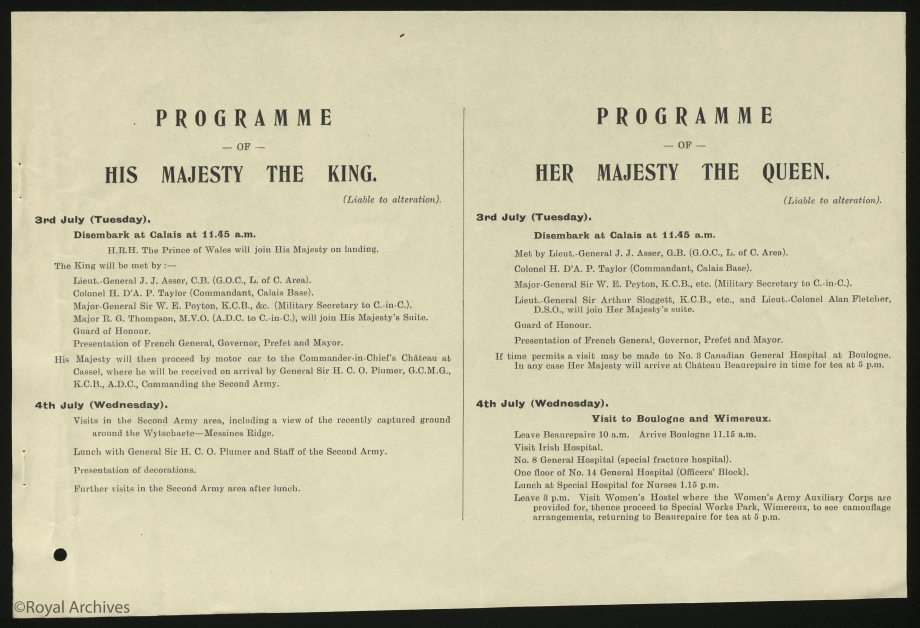

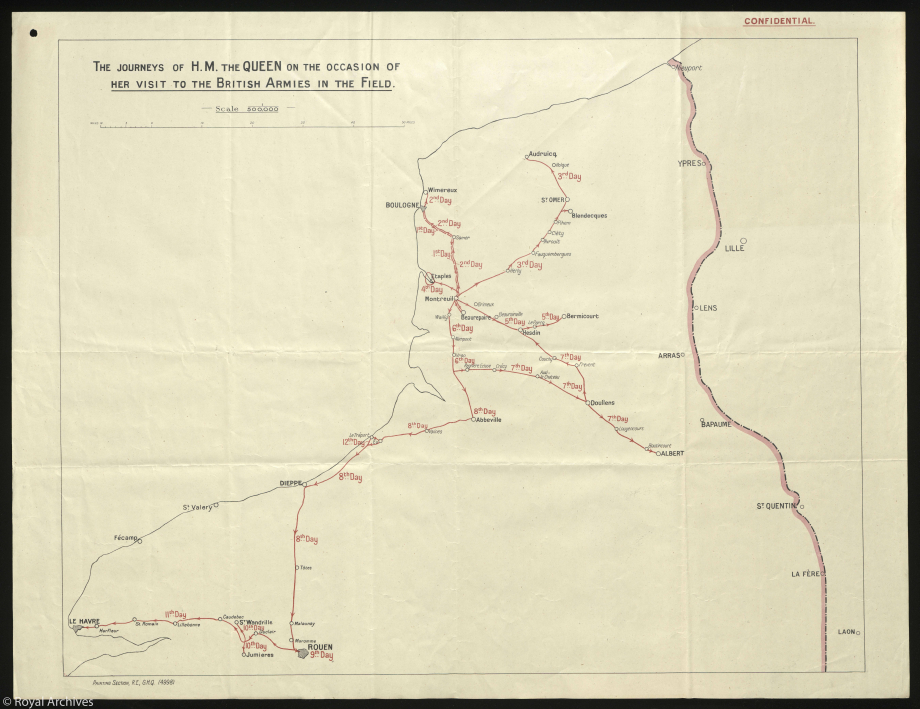

In July 1917 Queen Mary accompanied King George V on his visit to the frontline. Their Majesties arrived in France on 3 July, undertaking an extensive twelve day tour, meeting the troops. The first page of Their Majesties programme can be seen below.

This map shows the route which Queen Mary took during her visit to the Armies in the field. The line of the British trenches can clearly be seen on the right of the image.

On 4 July 1917, following a visit to Boulogne, Queen Mary met 1,500 soldiers who were returning from the Lens front on their way to a Rest Camp at Wimereux.

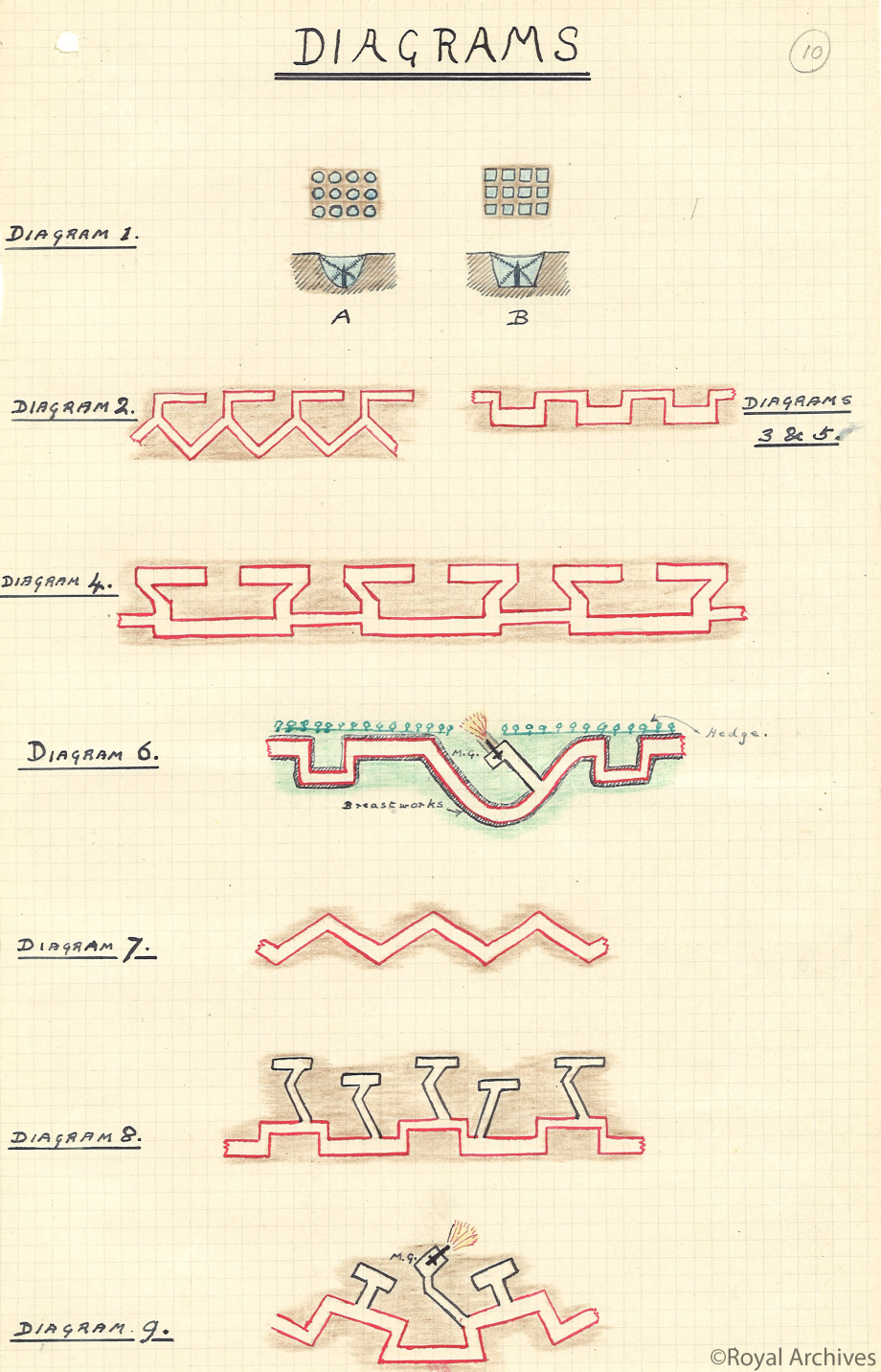

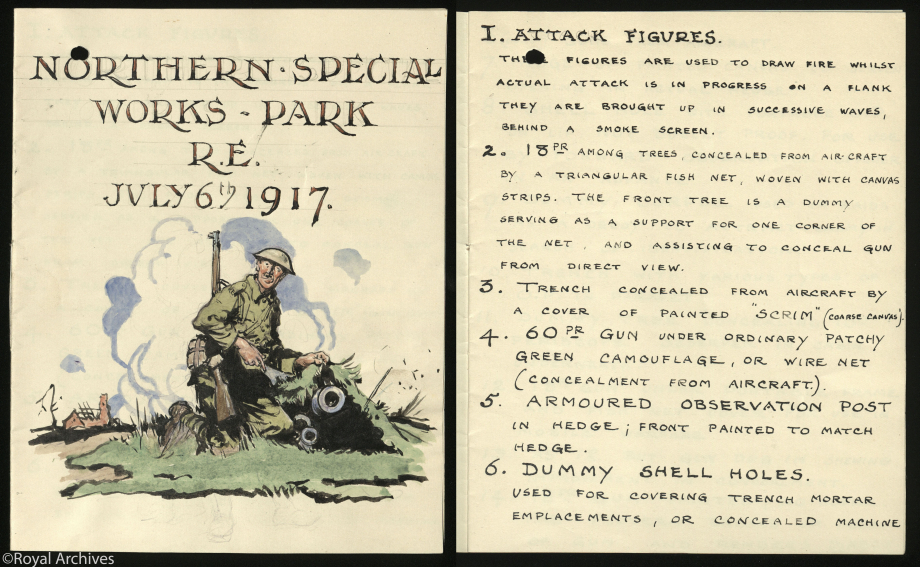

On the 6 July 1917, The King visited the Northern Special Works Park of the Royal Engineers, situated between Wormhout and Wylder, where he was shown the latest camouflage techniques. The King was given the below handwritten booklet which lists the objects included in the exhibition, although unfortunately the artist remains unknown.

The Home Front

Factory and Hospital Visits

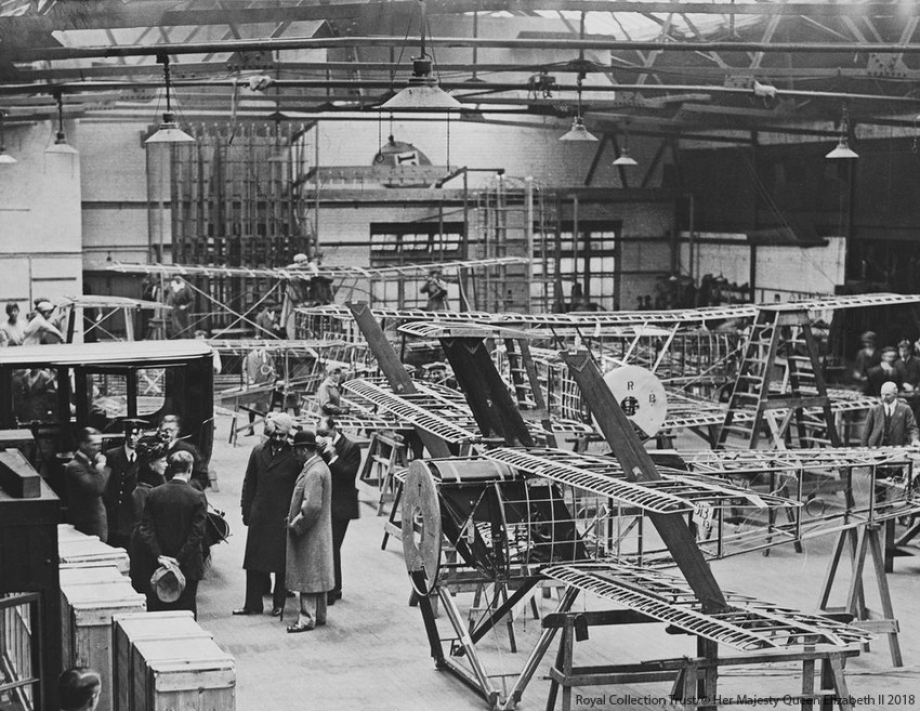

During the course of the war, The King and The Queen toured hundreds of factories, shipyards and hospitals across Britain. On 19 April 1917 The King and Queen visited the Sopwith Aviation Company works at Kingston-on-Thames, where they were shown around the factory by Thomas Sopwith.

The King records in his diary: "In the afternoon May & I paid a visit at Kingston-on–Thames to the works of the Sopwith Aviation Co. Sopwith showed us around, they turn out about 12 machines a week. We then motored to Brooklands flying ground where he showed us his latest machine which is a wonder, it is a single seater & goes 130 miles an hour, we saw his pilot (an Australian) fly it, he looped the loop & made spinning dives".

The King and Queen also undertook solo visits, and on 18 September 1917 The Queen, accompanied by Princess Mary, visited Coventry "to see Munition girls at work. Arrived 11.20 met by the Mayor and Mayoress & went to White Poppe's works which meant we went over & saw Machine Shop, Ambulance Room, Recreation hall etc."

The above photo shows Queen Mary looking happy while being pushed along in a munitions trolley, during her visit to a munition factory in Coventry, on 18 September 1917.

During 14-18 May 1917 King George V and Queen Mary toured Lancashire, visiting Liverpool, Lancaster and Manchester. On 16th The Queen visited the Manchester Royal Infirmary, where she talked to staff and patients.

The Opening of the State Apartments at Windsor Castle

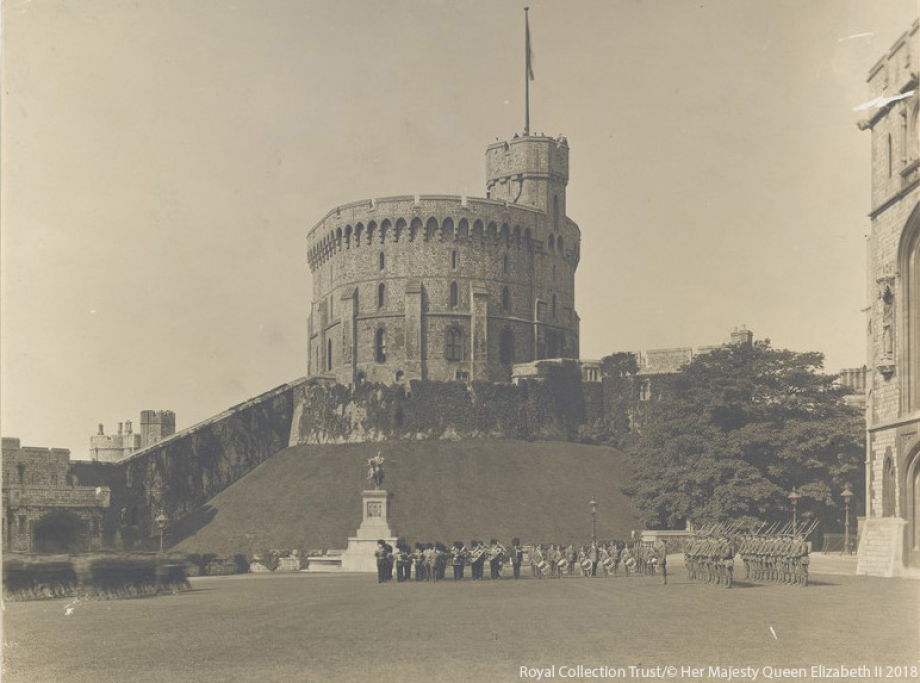

The State Apartments at Windsor Castle had been closed to the public since the beginning of the War. In 1917 King George V ordered that arrangements be made for officers and men of Overseas Forces, and wounded British Troops to be able to visit the State Apartments every Tuesday. Tickets of admission were issued by the Lord Chamberlain through the headquarters of the various Overseas Forces in London. Refreshments were provided under arrangements made by the Lord Steward's Department. Later in the year the privilege was extended to wounded British troops, and also to officers of the United States Army, passing through London.

The above photograph shows a military review at Windsor Castle during the First World War, in which soldiers from the Foot Guards and the Regimental band stand to attention, other soldiers can be seen marching across the Quadrangle.

Events at Buckingham Palace

The Royal Family hosted entertainments for wounded soldiers and sailors in the Riding School at Buckingham Palace during the First World War. Over three days in March 1916 more than 2000 men were able to attend these events.

On 24 March 1916, Queen Mary writes to her aunt, the Dowager Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (formerly Princess Augusta of Cambridge), describing these parties: "they had tea first in the Coach Houses, members of our family presiding at each table & being helped by the ladies & gentlemen of our household, & various friends of ours…The entertainment consisted of various artistes, acrobats, conjurors etc., an excellent choir singing songs of which the men knew the choruses, & sang them most 'heartily'. How you would have liked being present, it was all so informal, friendly and nice."

Queen Mary's Needlework Guild

During the First World War, Queen Mary's Needlework Guild organised gifts to be sent to soldiers and sailors abroad. In charge of proceedings, Queen Mary requested garments and parcels to be sent to Friary Court, St. James’s Palace for distribution to the frontline.

The above photo from 1917, was taken at St James' Palace during a presentation to Queen Mary from the British and Canadian Needlework Guild of gifts to be sent to overseas military personnel by its President, Princess Beatrice [The Queen's aunt-in-law]. On the Queen's left is her daughter Princess Mary.

On 3 March 1915, Brig-Gen. Harry Watson writes to the King's Private Secretary: "four big bundles of warm socks have lately arrived for my brigade…and to say how deeply indebted we all are to Her Majesty for the…kind thought of sending them. They are of infinite value to us"

Growing Potatoes

Towards the end of 1916, after a series of bad harvests, German blockades and the loss of vital shipping, the British Government decided that more need to be done to ensure that the country did not starve. One scheme encouraged people to grow their own vegetables.

The Royal Family embraced this initiative, setting aside an area of Frogmore Gardens for a potato plot. Queen Mary records in her diary on 24 April 1917: "We again went to Frogmore to finish planting our potato plot & worked from 3 to 5 – got very hot & tired".

Abstaining from Alcohol

By the spring of 1915, the disruptive effect of heavy drinking was causing great concern in the British Government, and they took measures to limit the amount of alcohol available. As an example to the nation, George V agreed to abstain from alcohol for the duration of the war.

Although as the King admits in his diary entry of 6 April 1915, hating the thought of it "we have all become teetotallers until end of the war, I have done it as an example, as there is a lot of drinking going on in the country, I hate doing it, but hope it will do good."

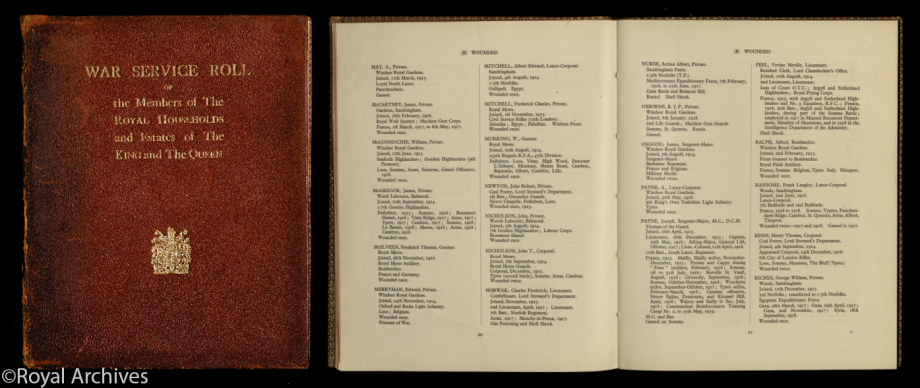

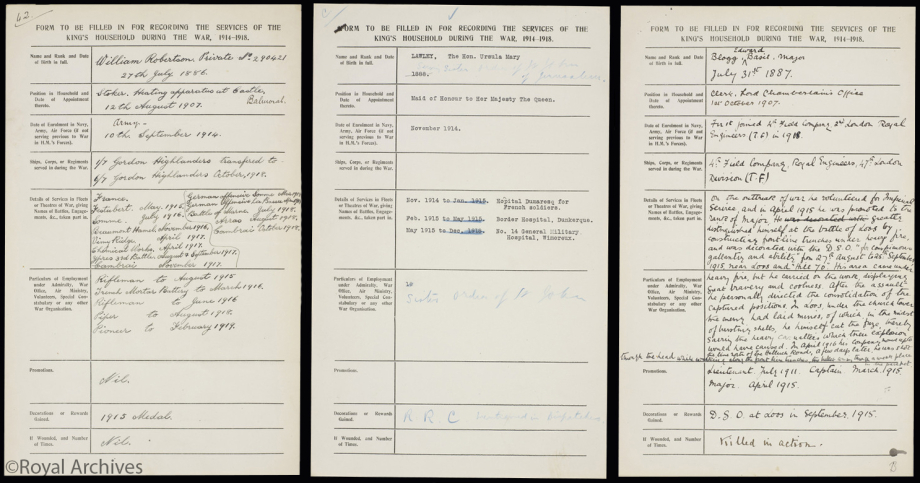

Royal Household Service Roll

During the First World War, 694 men and one woman from the Royal Household and private estates enlisted for military service. Many of the men from the Sandringham and Balmoral Estates joined The Norfolk or different Scottish regiments respectively; local Windsor men joined The Berkshire Regiment. Some of the London-based Household staff, including several footmen, also joined The Norfolk Regiment.

After the war, a document entitled ‘Form to be filled in for recording the service of the King’s Household during the war 1914-1918’ was produced as a means of recording individual war service for Royal Household employees. The information from these forms was used to create a booklet entitled ‘War Service Roll of the Members of The Royal Household and Estates of the King and the Queen’, which would act as a written memorial to those of the Royal Household who had served during the Great War, and was published by the Stationary Office:

- 143 men were killed whilst serving in the Army.

- 153 men were wounded, some returning to active service and others being discharged.

- 225 men saw active service and survived the War.

- 174 men served at home, including as Special Constables, recruiting and training, at supply depots and guarding the coastline.

The above forms show three members of the Royal Household who served.

Private William Robertson was appointed Stoker of the Heating apparatus at Balmoral Castle in 1907. In September 1914 he enlisted, serving in the Gordon Highlanders, and saw action during many of the large scale battles on the Western Front.

The Honorable Ursula Mary Lawley was appointed Maid of Honour to Queen Mary in 1912. In November 1914 she volunteered as a Serving Sister in the Order of St John, and during the war worked at a number of military hospitals in France. She returned to her pre-war role, relinquishing it in 1927.

Major Edward Basil Blogg was appointed Clerk in the Lord Chamberlain's Office in 1907. During the war he served in the Royal Engineers, having previously been part of their Territorial Force, and he was killed in action on 16 March 1916.

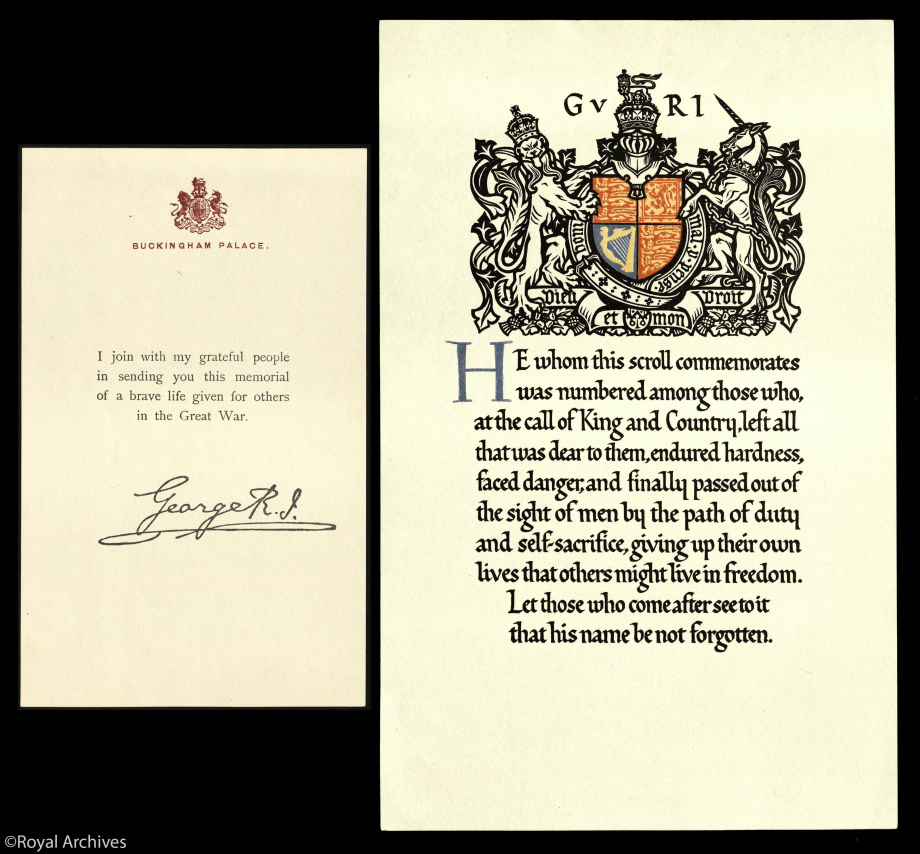

Scrolls and Plaques

The next of kin of all members of the British and Empire Forces who died in the First World War were sent a message, a scroll and a plaque, at the State's expense.

The message was printed on Buckingham Palace writing paper, and bore a facsimile of King George V's signature. The wording on the scroll was drafted by Dr. Montague Rhodes James, Provost of King's College, Cambridge, and the wood block from which the scroll was printed was cut by a group of artists attached to the London County Council Central School of Arts and Crafts, under the supervision of the Principal, F. H. Burridge.

A Government committee organized a competition in 1917 for the design of a plaque, and the winner was E. Carter Preston of Sandon Studies Society, Liverpool, whose design shows Britannia holding a trident and a myrtle wreath, with a lion standing at her feet and dolphins playing on either side. Around the edge is the inscription "He died for freedom and honour", and below Britannia's left hand is a space for the name of the dead man. The artist's initials, E.C.P., appear by the lion's forepaws. These bronze plaques, almost 5 inches in diameter, were produced from December 1918 onwards, first of all at a factory in Acton, but later at Woolwich Arsenal and other centres no longer engaged in munitions production.

From 1919 onwards some 1,150,000 scrolls and plaques were issued. The scrolls and messages were sent out in cardboard rolls, the plaques separately in cardboard containers in white envelopes bearing the royal crest. They were sent to commemorate those who died between 4 August 1914 and 10 January 1920 for Home Establishments, Western Europe, and the Dominions, whilst the final date for other theatres of war, or for those who died subsequently from attributable causes, was 30 April 1920. Messages for those from the Dominions, India, and the Colonies were sent by the respective Governors General, Viceroys, and Governors.

Armistice Day

At 11am on the 11 November 1918, the First World War officially came to an end. The announcement was met with obvious joyous celebrations across the nation, and crowds of people started to converge on Buckingham Palace. Their Majesties made many balcony appearances throughout the day, and in the afternoon undertook an open top carriage drive through the city in the pouring rain.

Queen Mary records in her diary her thoughts on this momentous day:

"The greatest day in the world's history. The armistice was signed at 5. a.m. & fighting ceased at 11. U. Arthur came to breakfast, & at 11. we went on to the balcony to greet the large crowd which had formed outside. At 12.30. we went out again & the massed bands of the Guards played the National Anthem & patriotic songs, & the anthem of the Allies. Huge crowds & much enthusiasm…At 3.15 we drove to the City in the pouring rain & had a marvellous reception. The members of the family came to tea & then some WAACS, WRENS etc. came & sang patriotic songs. So nice of them. The Prime Minister came to see us at 7. U Arthur & Patsy came to dinner, afterwards we went on to the balcony, the band played popular songs, & we had another wonderful scene. A day full of emotion & thankfulness – tinged with regret at the many lives who have fallen in this ghastly war."

Above is the flag Queen Mary waved on Armistice Day, during one or more of The Royal Family's many balcony appearances.

King George V records in his diary his thoughts on this momentous day:

"Today has indeed been a wonderful day, the greatest in the history of this Country. At dawn the Canadians took Mons which was the place that we first came in contact with the Germans over 4 years ago & from where the retreat began. At 5. a. this morning the armistice was signed by Foch, Wemyss & the German delegates & hostilities ceased at 11.0. Uncle Arthur came to breakfast. The news spread quickly & a large crowd assembled outside & May & I & Uncle Arthur went on the balcony when the Guard marched off…At 1.0. we again went on the balcony, there was an enormous crowd who gave us a wonderful reception, the Guards massed bands played all the National anthems of the Allies & a few popular ones, it was an extraordinary sight. In afternoon although it unfortunately rained we drove with Mary & Cust in open carriage by the Strand to Mansion House & home by Piccadilly, there was a vast crowd, most good humoured, in some places it was hardly possible to get along…Worked all evening, hundreds of telegrams coming from all parts. Uncle Arthur & Patsy dined with us. Showed ourselves on the balcony as there was still a large crowd, the Irish Guards band played."

Unveiling the Cenotaph

On the 11 November 1920 King George V unveiled the Cenotaph, the national memorial to the 'Glorious Dead' of the 1914-1918 war, and afterwards Their Majesties attended the burial service for the 'Unknown Warrior' in Westminster Abbey.

King George V reflects in his diary on this affecting occasion:

"…Today I unveiled the Cenotaph in memory of the "Glorious Dead" in Whitehall & was Chief Mourner at the burial of an "Unknown Warrior" in Westminster Abbey. At 10.15 we all motored to the Home Office, the Ladies went to windows, & I with the three boys received the body at the Cenotaph, which had been brought from France yesterday & the funeral procession came from Victoria station. At 11.0. I unveiled the Cenotaph & then followed two minutes silence throughout the whole Empire. The whole ceremony was most moving & impressive. I then followed the gun carriage on foot to Westminster Abbey where the burial took place, the grave was filled in with soil brought from France. The Service was beautiful & conducted by the Dean. All the Ministers headed by the Prime Minister & Mr Asquith walked in the procession beside a large number of representatives of the three Services. Got home at 12.0. everything was most beautifully arranged & carried out…"

Queen Mary records her feelings on this poignant day:

"At 10. the body of the "unknown warrior" passed along constitution hill. At 10.20 we motored to the Home Office. G & the boys went to the Cenotaph while Mary & I joined Mama & the others at a window. The short ceremony below while the Cenotaph was unveiled by G was most impressive & the 2 minutes silence had a wonderful effect. We then went to Westminster Abbey to await the arrival of the body & were present at the internment. Wonderful service but most upsetting. Home after 12…"

[embed_content nid="66490" show_title="true" show_submitted="true" show_meta="true" show_terms="true" show_links="true"][/embed_content]

Programme for the burial of the "Unknown Warrior" in Westminster Abbey on 11 November 1920.

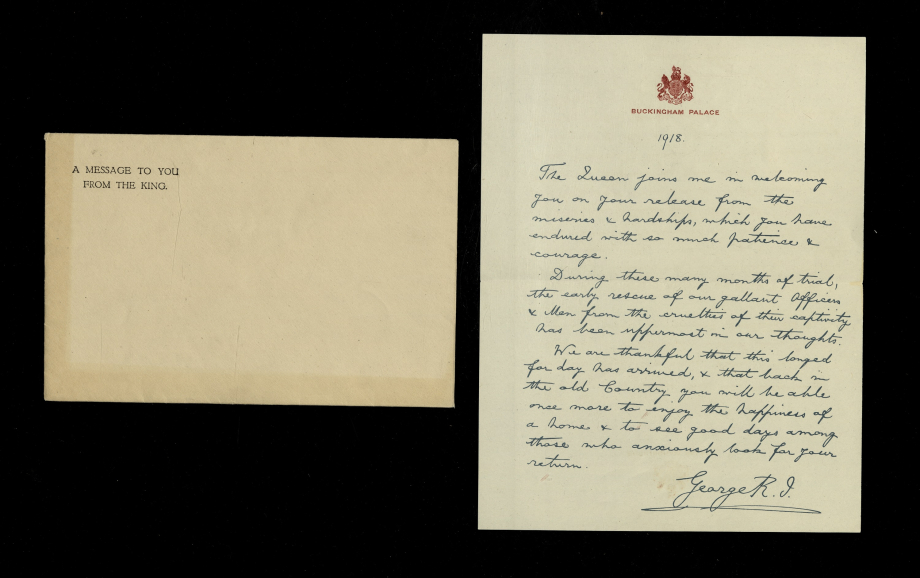

Returning troops

All British, Dominion and Colonial prisoners of war returning home after the end of the First World War received a lithograph copy, on Buckingham Palace writing paper, of an original message written by King George V. Although '1918' was written at the top, those men who did not return until 1919 still got a copy of this letter. Distribution was arranged by the Mobilisation Department and by the Central Prisoners of War Committee, which ensured that all former prisoners arriving at reception camps or at hospitals received their copy of the letter. The King requested that each man's name be written on the letter. There is no record in the Royal Archives of the names or numbers of those to whom the message was given.

On 3 December 1918 Queen Mary went to Cannon St Station “…to meet some of the repatriated prisoners of war from Belgium chiefly – I spoke to a good many men – they looked fairly well but then they have been well fed & looked after for the past few days which makes all the difference…”

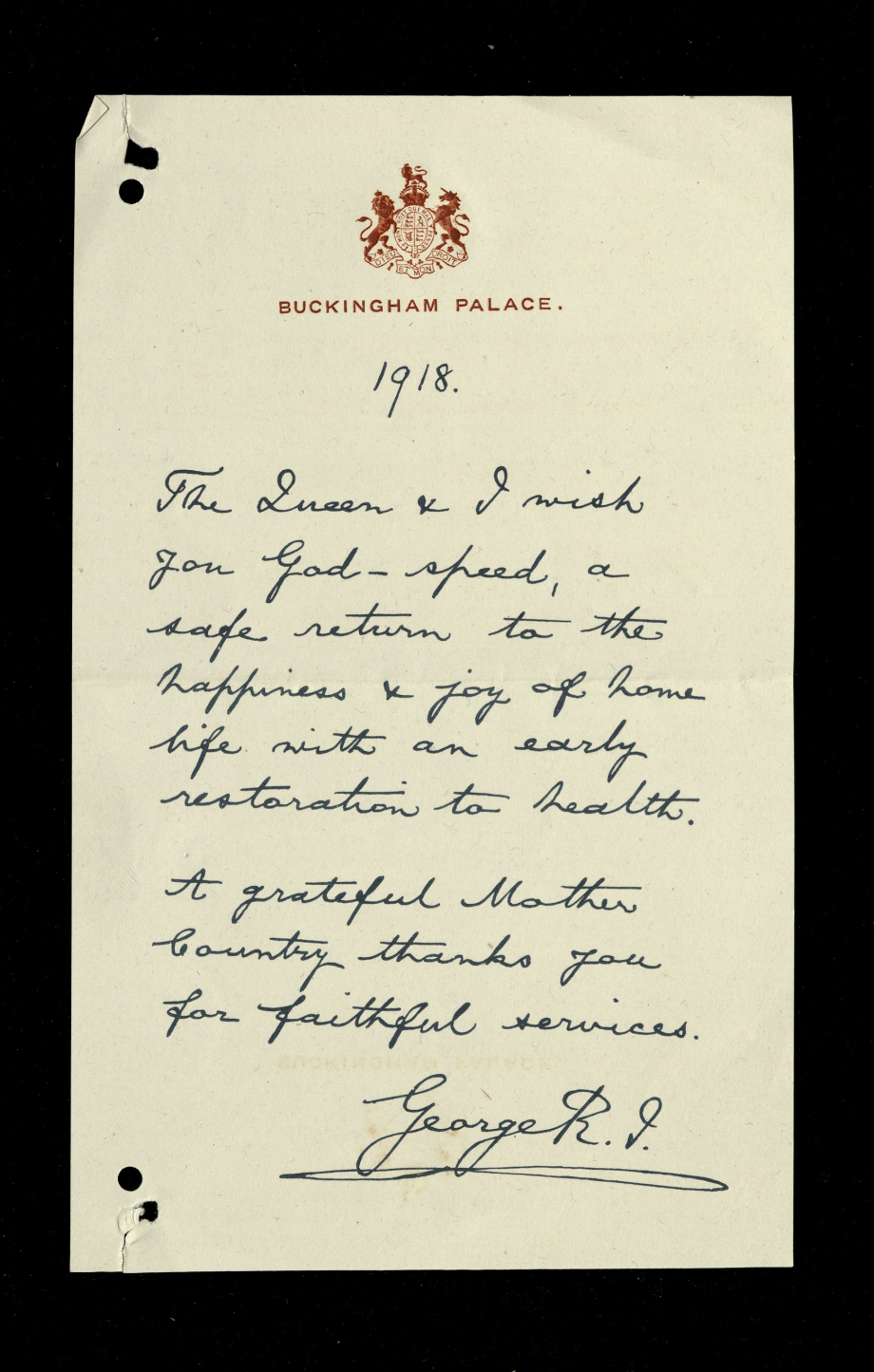

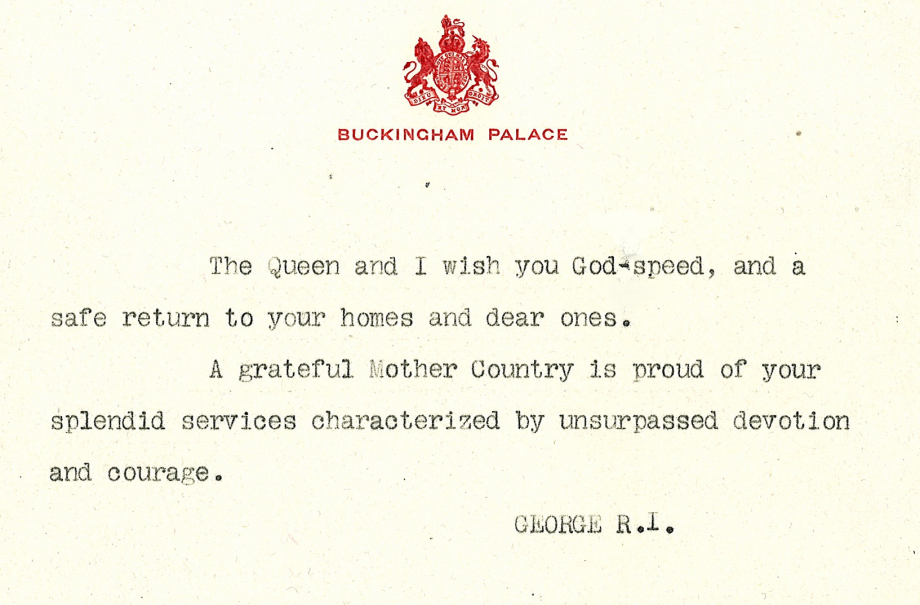

Soldiers from the Dominions and Colonies, who were sick or wounded, received the message below from the King and Queen prior to their departure home. The King requested that each man’s name be written on the message or envelope.

Text of the message sent by the King and Queen to all other soldiers from the British Empire received prior to their journey home.

The King's Pilgrimage 1922

In around 1920-1921 the Imperial War Graves Commission [IWGC] began the construction of permanent cemeteries, across France and Belgium, for servicemen from Britain and her Empire. In many cases smaller gravesites were closed and amalgamated into larger cemeteries.

In May 1922 King George V and Queen Mary undertook a State Visit to Belgium. As part of this visit the King undertook a three-day tour of the battlefield cemeteries accompanied by Sir Fabien Ware [Vice-Chairman of the IWGC], Field Marshal Douglas Haig and Admiral David Beatty. This three day tour soon became known as ‘The Kings Pilgrimage’.

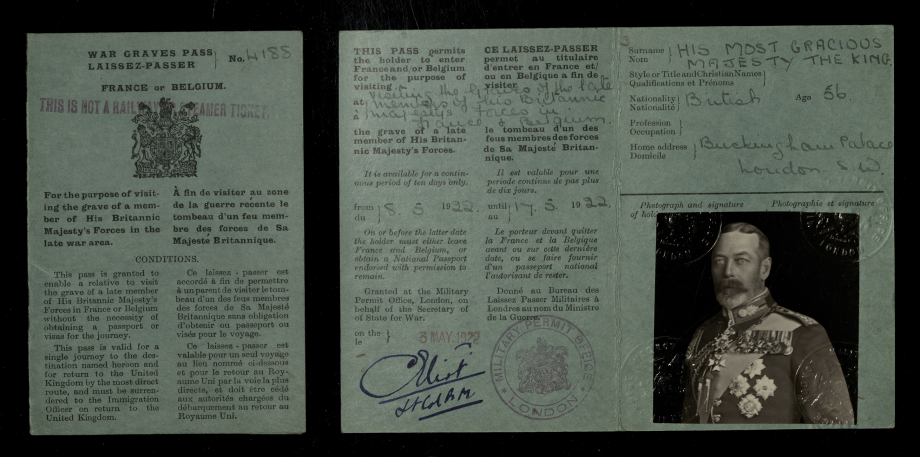

These two passes were issued to King George V to allow him to visit the war graves in 1922. These passes were to enable close relatives to visit the grave of a fallen family member in France and Belgium without the need for a passport. It is not clear why two separate passes were issued other than the King is wearing the uniform of the Royal Navy in one and the Army in the other.

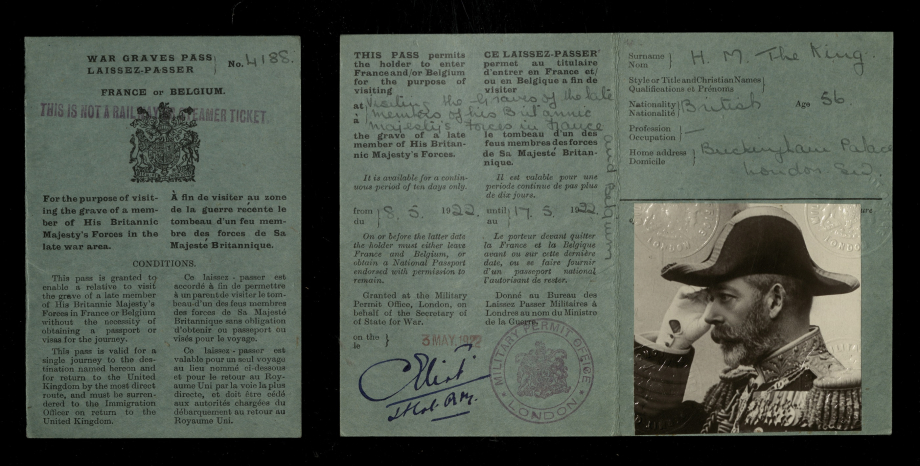

These maps showing the location of the IWGC cemeteries visited by King George V on 12 and 13 May 1922. The cemeteries at Tyne Cot, Poperinghe, Meercut Indian Cemetery and Terlincthun are shown in the first image.

On 11 May 1922, King George V recorded in his diary his visits to military cemeteries in Belgium:

'I left at 9.0 in my train with Haig & Sir Fabien Ware (Permanent Vice Chairman of the Imperial War Graves Commission), Fritz, Wigram & Seymour for Zeebrugee where I arrived at 11.0. Went to see the German cemetery where some English are buried, visited the mole & left at 12.40. Luncheon in the train. Arrived at Zonnebeke at 2.30. Left in motors & visited the British cemeteries at Tyne Cot, Ypres, Vlamertinghe, Hop Store, Brandhoek, Poperinghe & Lijssenthoek. Joined the train at Poperinghe & left at 6.10. At each I was received by the Mayor & a crowd of people. The cemeteries are very well arranged & looked after by ex service men under the Commission. Very interesting passing through all the battle area, nearly all the houses have been rebuilt…'

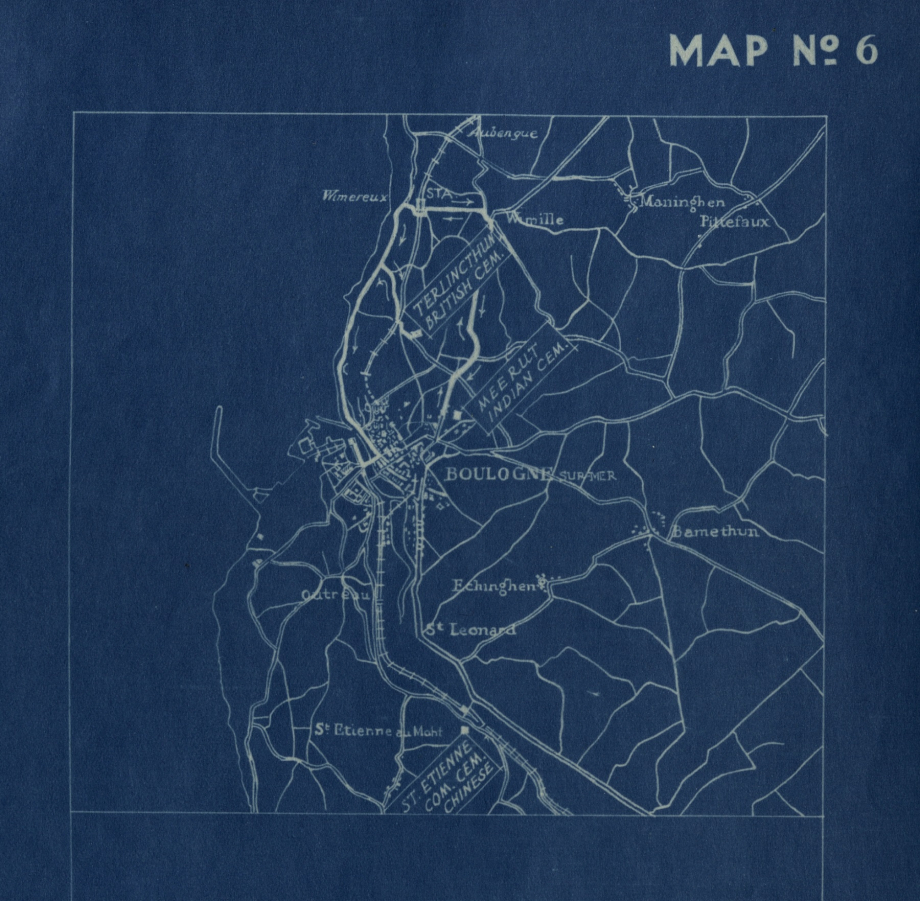

At Terlincthun cemetery the King made a speech stating that:

“…we remember, and must charge our children to remember, that, as our dead were equal in sacrifice, so are they equal in honour, for the greatest and the least of them have proved that sacrifice and honour are no vain things but truths by which the world lives…and I fervently pray that, both as nations and individuals, we may so order our lives after the ideals for which our brethren died that we may be able to meet their gallant souls once more, humbly but unashamed."

King George and Queen Mary visited the Imperial War Graves Commission cemetery at Terlinchtun on 13 May 1922. Relatives of the buried soldiers can be seen in the background.