Cromwell's convincing military successes at Drogheda in Ireland (1649), Dunbar in Scotland (1650) and Worcester in England (1651) forced Charles I's son, Charles, into foreign exile despite being accepted and crowned King in Scotland.

From 1649 to 1660, England was therefore a republic during a period known as the Interregnum ('between reigns'). A series of political experiments followed, as the country's rulers tried to redefine and establish a workable constitution without a monarchy.

Throughout the Interregnum, Cromwell's relationship with Parliament was a troubled one, with tensions over the nature of the constitution and the issue of supremacy, control of the armed forces and debate over religious toleration.

In 1653 Parliament was dissolved, and under the Instrument of Government, Oliver Cromwell became Lord Protector, later refusing the offer of the throne.

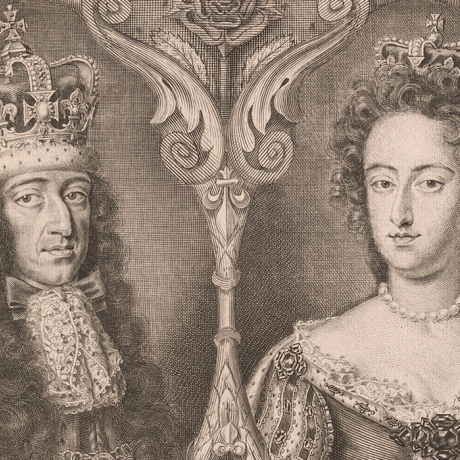

Further disputes with the House of Commons followed; at one stage Cromwell resorted to regional rule by a number of the army's Major Generals. After Cromwell's death in 1658, and the failure of his son Richard's short-lived Protectorate, the army under General Monk invited Charles I's son to become King as Charles II.