Each day for the next nine days, we'll be sharing an item from the Royal Archives according to the themes set by The Archives and Records Association. We hope that these unique and rarely-seen items help you understand more about the work of the Archives and the documents they preserve, as well as the history and work of the Royal Family.

Day Nine: 'Your Archive'

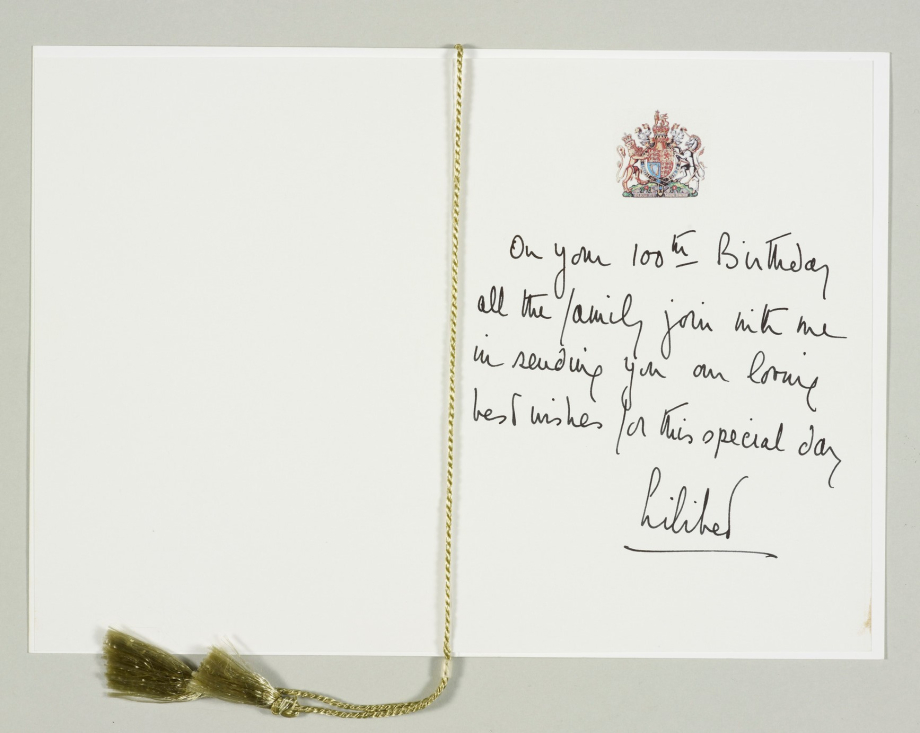

Since 1917 it has been customary for the Sovereign to send a message of congratulations to those celebrating his or her 100th and 105th birthdays and every year thereafter. Such messages were sent on rare occasions during the reign of King Edward VII, but the practice became more regularised during the reign of King George V. The message was originally in the form of a telegram, but these were replaced by telemessages (a combination of telegram and letter) in 1982, and later, in 1999, by a card which includes a picture of The Queen and her signature in facsimile.

On 4 August 2000, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother celebrated her 100th birthday, and that morning, a congratulatory card from her daughter, Queen Elizabeth, was duly delivered to Clarence House. The card was the same as those sent to centenarians up and down the country, but contained a personal message signed ‘Lilibet’, the pet name given to The Queen by her parents. This 100th birthday message celebrates the grand age of a much-loved member of the Royal Family, yet it was also a rare example of The Queen acting in both her roles as daughter and Sovereign.

Day Eight: Humour

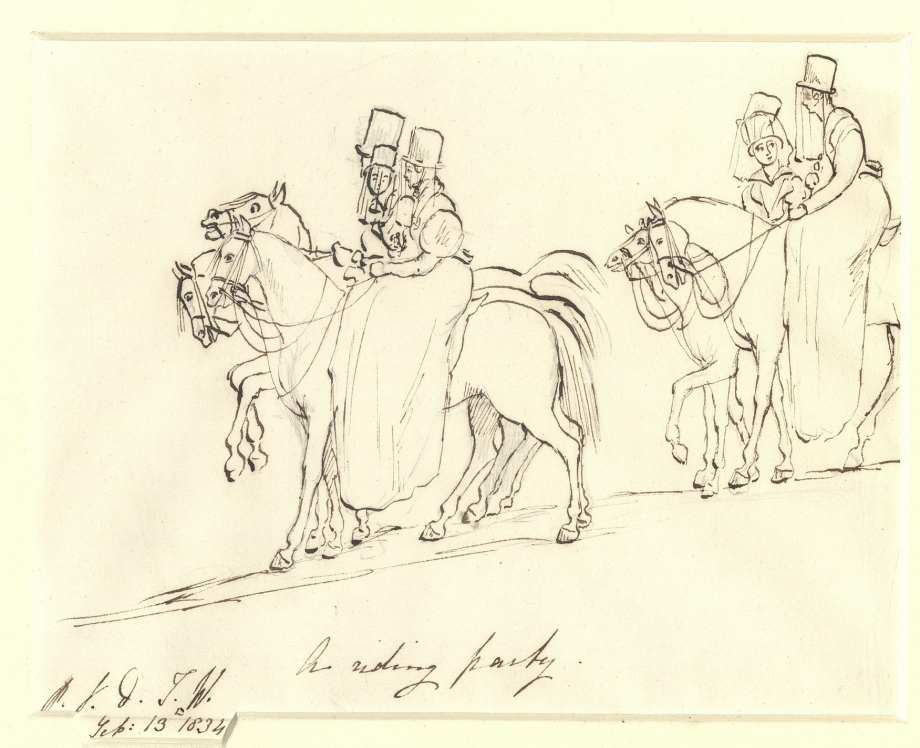

Princess Victoria (later Queen Victoria) began writing a journal – or detailed diary in 1832, when she was thirteen years old. Although this began as an educational exercise, it clearly became a pleasure for her, and from that time onwards she wrote her journal almost every day, with only a few short breaks when she was ill, until shortly before her death in 1901. As well as being a great diarist, the Queen was also a keen amateur artist, and her journal entries were often illustrated by sketches, mostly drawn by the Queen herself. She also compiled many albums of her sketches, drawings and watercolours of the people and places about which she had written in her journals. The above sketch of a ‘riding party’ was drawn by Princess Victoria in 1834.

Queen Victoria is reputedly to have said ‘We are not amused’ although we have found no proof of this exact phrase in the archives, there are references to her being amused in her journal. Queen Victoria records in her journal an occasion where she fell off her horse during a ride in Windsor Great Park on 8 September 1838, remarking that she was “not a bit hurt, or put out, or frightened, but astonished and amused….”

“…We rode round Virginia Water. As I was galloping homewards, before we came to the Long Walk, on the grass, and not very fast, Uncle [Leopold] left my side and I went alone with Lord Melbourne, when something frightened Uxbridge, who was alarmed at being left without his 2nd companion, and he swerved against Lord M’s horse so much, that I came off; I fell on one side sitting, not a bit hurt, or put out, or frightened, but astonished and amused, and was up, and laughing before Col. Cavendish and one of the gentlemen, all greatly alarmed, could come near me, and said ‘I am not hurt’….”

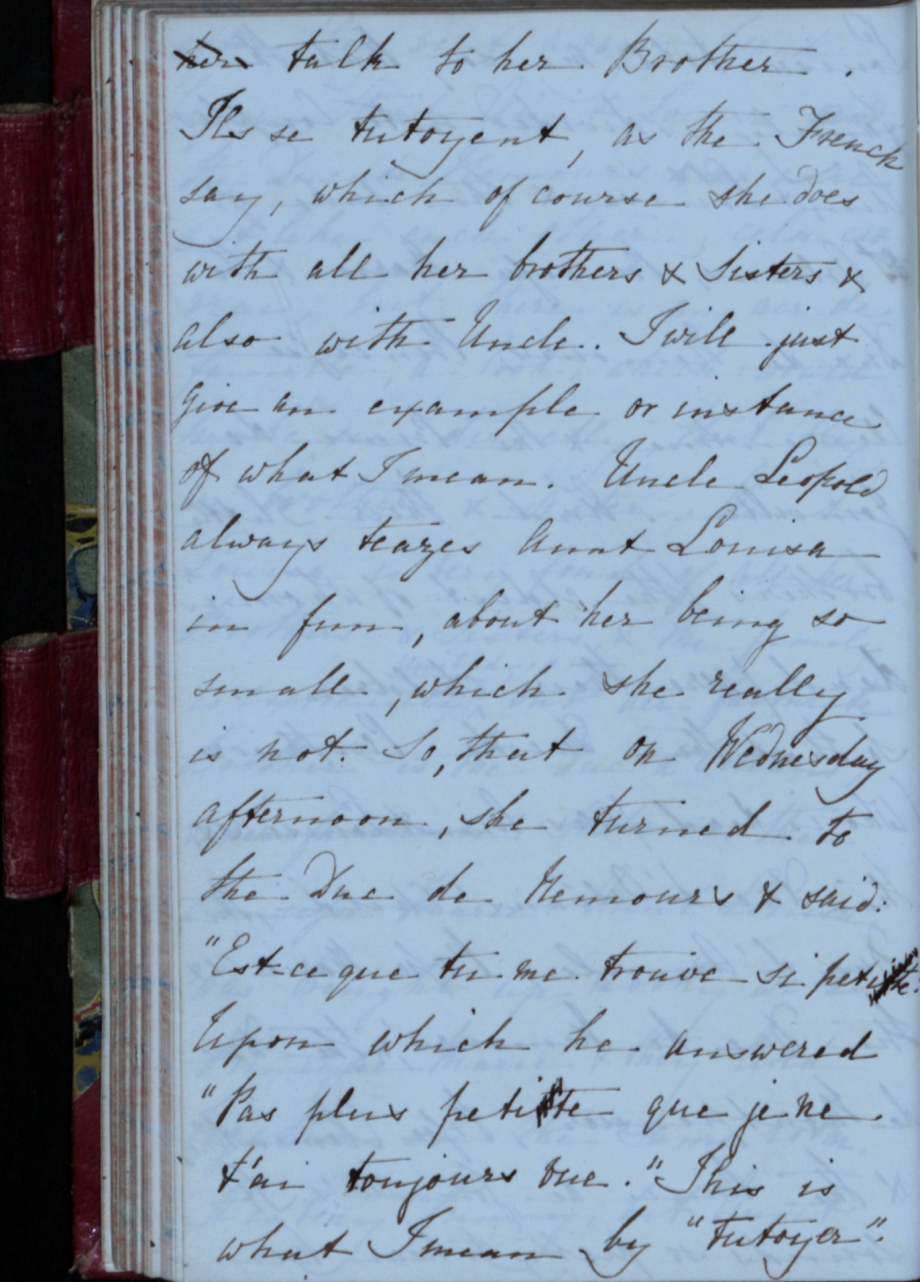

Day Seven: Languages

Queen Victoria began learning French as a child, and was fluent by the time she was an adult.

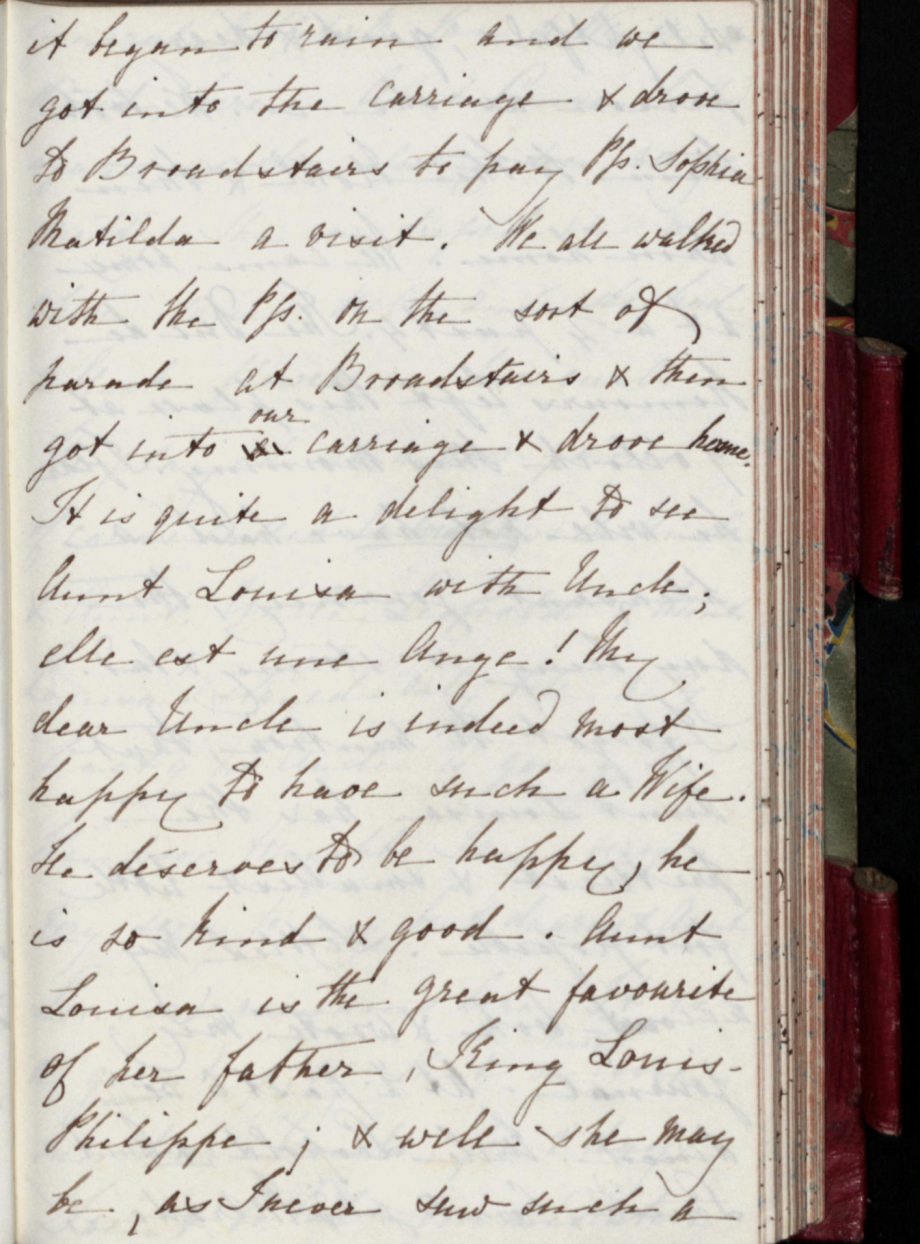

On 1st October 1835 she recorded a family outing with ' Uncle Leopold and dear Aunt Louisa’ , King and Queen of the Belgians. Her aunt was also the daughter of Louis Philippe I, King of the French. Victoria seemed very taken by her aunt and peppers her diary entry with French words describing her fondness for her.

'It is quite a delight to see Aunt Louisa with Uncle; elle est une Ange (she is an angel)! My dear Uncle is indeed most happy to have such a Wife. He deserves to be happy he is so kind and good. Aunt Louisa is the great favourite of her father, King Louis Philippe; and well she may be, as I never saw such a delightful, good and dear person as she is.'

The party were later joined by her aunt's brother, the Duc de Nemours:

'I said before that Aunt Louisa and the Duc de Nemours were not like each other; cela est vrai, but there is an air de famille (that is true, but there is a family resemblance).'

Victoria describes their sibling humour, and that brother and sister spoke to each other using 'tu' for 'you' rather than the formal 'vous'.

'Ils se tutoyent, as the French say, which of course she does with all her brothers and sisters and also with Uncle. I will just give an example or instance of what I mean. Uncle Leopold always teazes Aunt Louisa in fun, about her being so small, which she really is not. So that on Wednesday afternoon, she turned to the Duc de Nemours and said: “Est-ce que tu me trouve is petite? (do you think I'm small?)” Upon which he answered, “Pas plus petite que je ne t'ai toujours vue (no smaller than you've always been)”. This is what I mean by “tutoyer”.'

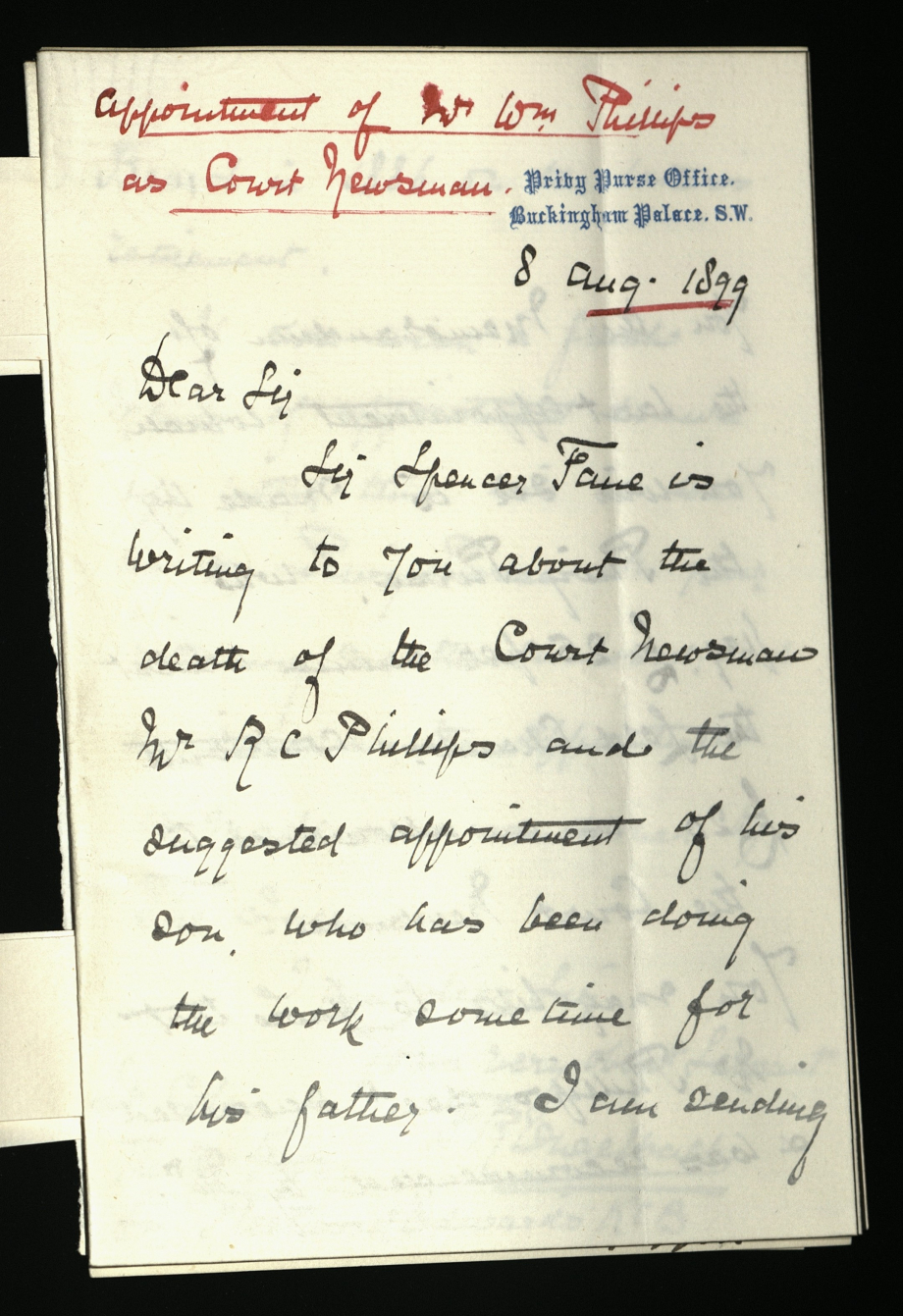

Day Six: News

During his reign, George III, apparently much annoyed at the inaccuracies published by the newspapers in relation to royal events, appointed a Court Newsman. The Newsman’s role was to distribute to the morning papers the ‘Court Circular’ each day - a document supplied by the Court which recorded royal activities. The Court Newsman received a salary paid by the Lord Chamberlain’s Office and the Privy Purse (recorded in 1886 as being £45). Newspapers also paid the Newsman for the information he provided and were reliant on him to ensure its accuracy.

In 1918, the role was replaced by a full-time Press Secretary until 1931 when the post was abolished and press matters were dealt with by the Assistant Private Secretary. In 1944 the heavy workload led to the re-appointment of a Press Secretary, assisted by a Lady Clerk, and the Press Office at Buckingham Palace was established. Today, the Court Circular is published in selected British newspapers and on the Monarchy website, and it is written by an Information Officer based in the Private Secretary’s Office at Buckingham Palace.

Letter from F R Engelbach (Clerk to the Privy Purse) to Sir Fleetwood Edwards (Keeper of the Privy Purse) concerning the appointment of William Phillips as the Court Newsman, who was taking over the role from his father, Robert C Phillips. Queen Victoria duly approved his appointment as Court Newsman.

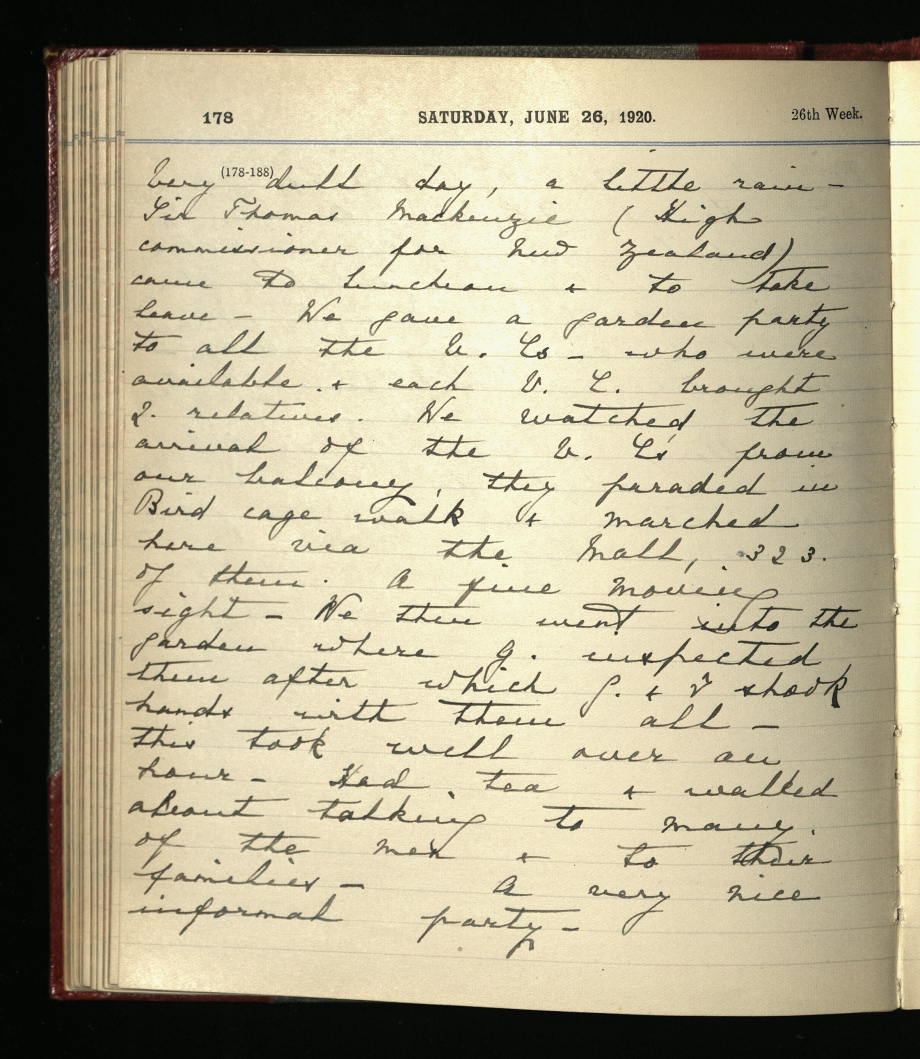

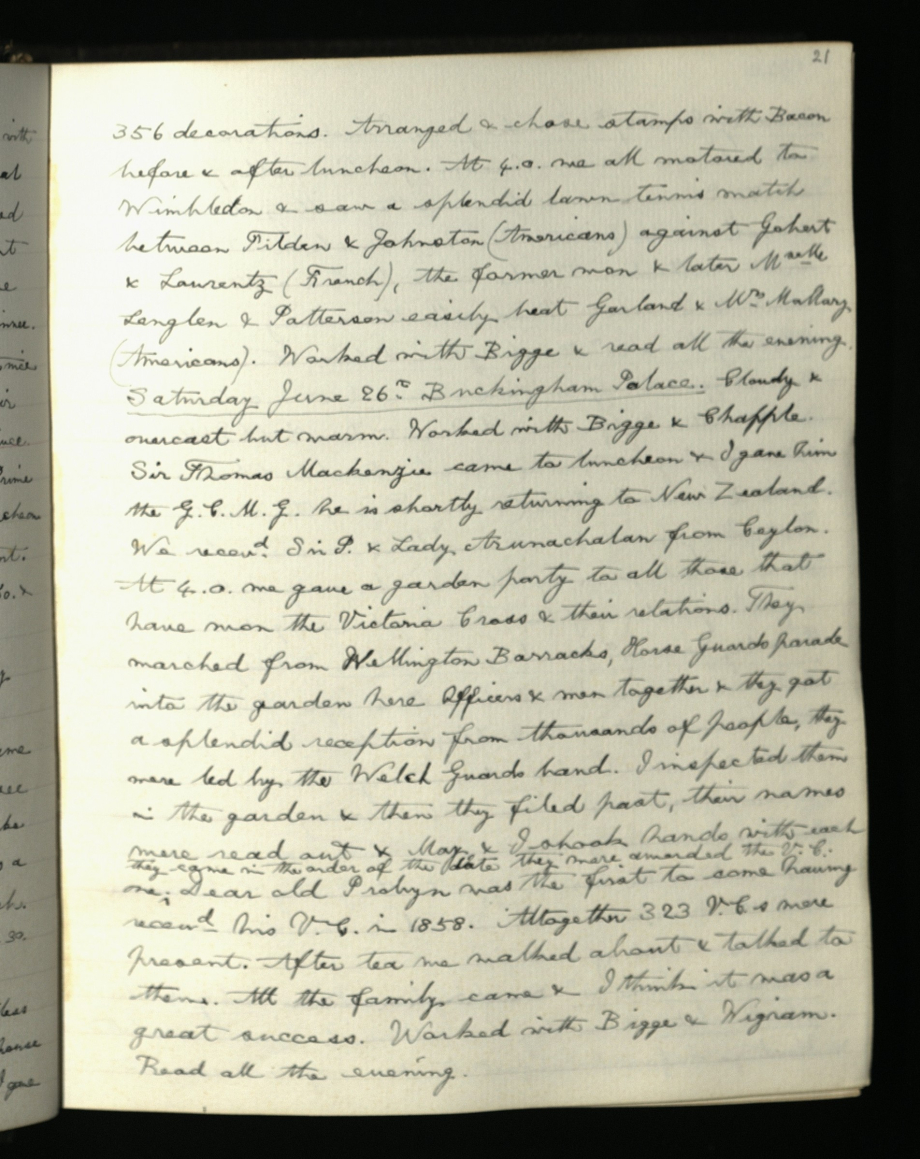

Day Five: Party

The On 26 June 1920 a Garden Party was held at Buckingham Palace for recipients of the Victoria Cross. Although all remaining recipients were invited, only 323 were able to attend on the day. Both King George V and Queen Mary much enjoyed the occasion as can be seen by their respective diary entries.

In her diary entry on 26 June 1920, Queen Mary wrote :

“….We gave a garden party to all the V.Cs who were available & each V.C. brought 2 relatives. We watched the arrival of the V.Cs from our balcony, they paraded in Bird cage walk & marched here via the Mall, 323 of them. A fine moving sight. We then went into the garden where G. inspected them after which G. & I shook hands with them all - this took well over an hour. Had tea & walked about talking to many of the men & to their families. A very nice informal party.”

King George V also recorded the event in his diary:

“….At 4.0. we gave a garden party to all those that have won the Victoria Cross & their relations. They marched from Wellington Barracks, Horse Guards parade into the garden here Officers & men together & they got a splendid reception from thousands of people, they were led by the Welch [Welsh] Guards band. I inspected them in the garden & then they filed past, their names were read out & May & I shook hands with each one, they came in the order of the date they were awarded the V.C. Dear old Probyn was the first to come having received his VC in 1858. Altogether 323 V.Cs were present. After tea we walked about & talked to them. All the family came & I think it was a great success…”

Day Four: Throwback

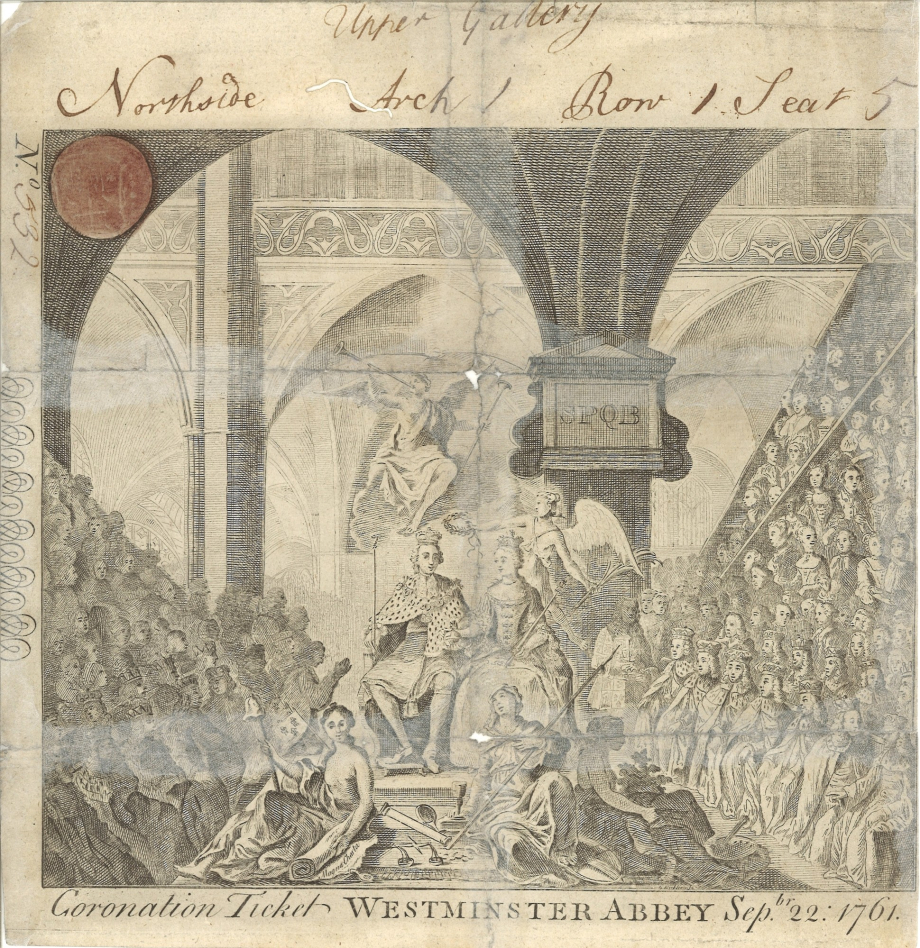

Admission ticket for the Upper Gallery of Westminster Abbey for the Coronation of King George III and Queen Charlotte on 22 September 1761. The ticket is highly decorative and depicts the crowned King and Queen, under a vaulted dome in Westminster Abbey, while a multitude of ermine-robed dignitaries and spectators view the ceremony.

The Coronation of King George III and Queen Charlotte took place on 22 September 1761 at Westminster Abbey. The ceremony lasted many hours, and as the Archbishop of Canterbury climbed into the pulpit to deliver the sermon, many of the congregation took the opportunity to eat the food and wine that they had brought with them, resulting in the noisy clattering of plates, glasses and cutlery.

Day Three: Beards

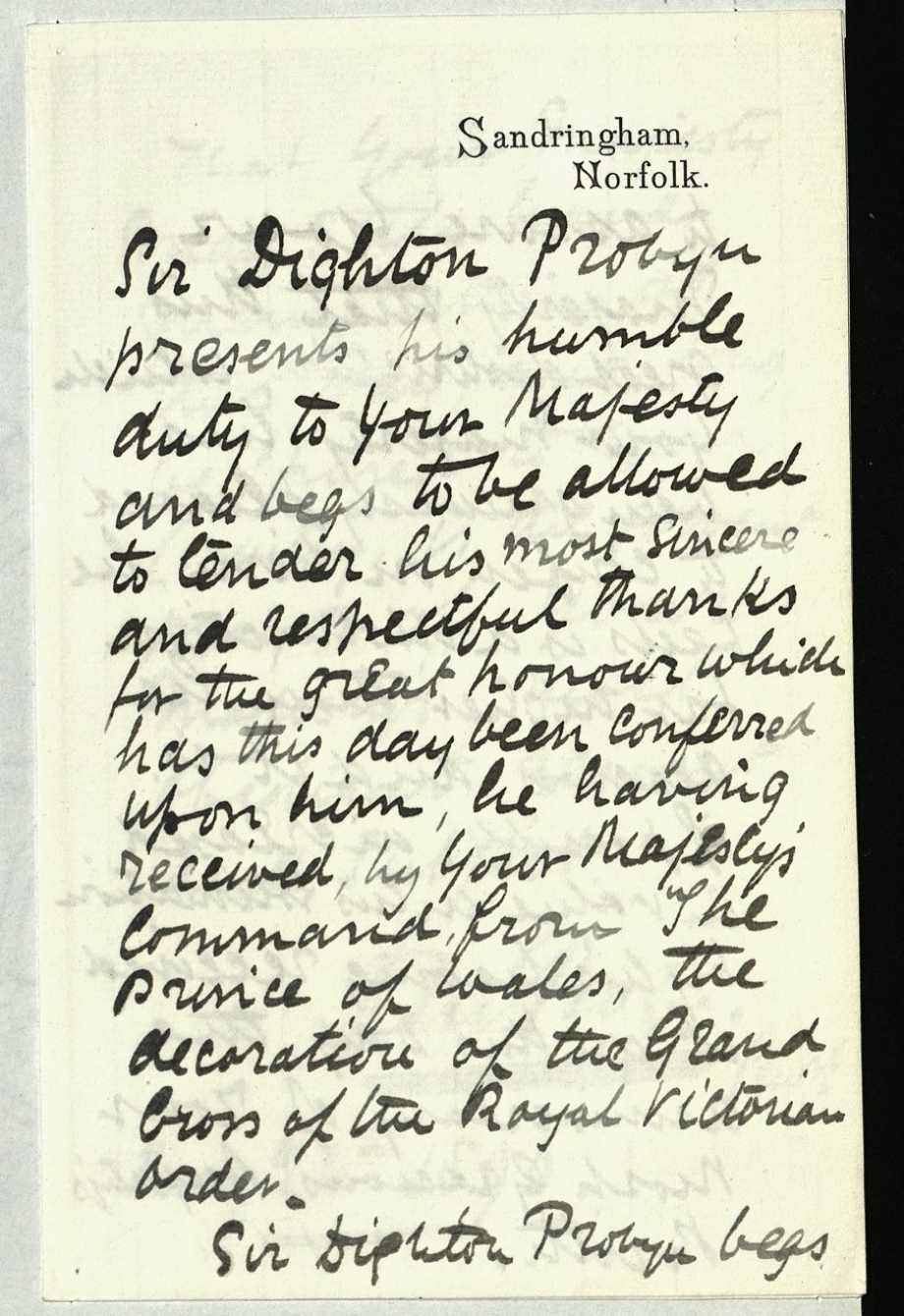

On 24 May 1896, General Sir Dighton Probyn writes to Queen Victoria expressing his gratitude for his appointment as Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order. Probyn would later become Comptroller in Queen Alexandra's Household, and can be seen in this photograph, resplendent of beard, sitting next to Queen Alexandra.

“Sir Dighton Probyn presents his humble duty to Your Majesty and begs to be allowed to tender his most sincere and respectful thanks for the great honour which has this day been conferred upon him, he having received by your Majesty’s Command, from The Prince of Wales, the decoration of the Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order….”

Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2022

Day Two: Time

King George III took a great interest in the science of his day, as well as developments in astronomy, and was fascinated by scientific instruments and clocks. A number of the scientific instruments he collected are now kept in the Science Museum. This undated manuscript, in the hand of King George III, lists the correct sequence of operations for mounting a watch. Another manuscript, entitled ‘Directions for unmounting a Watch’, records the opposite procedure.

Directions for Mounting a Watch

On the Under Plate place the Barrel

then the fusee or Great Wheel

then the Third Wheel

the Contrate Wheel

the Center Wheel

fix the Upper plate

place the third Wheel into the Upper plate

place the Contrate Wheel

put in the pins of the Pillars that fasten

the two Plates together

Hook the Chain into the Barrel

Mount the Main Spring put your finger on the

Barrel to prevent the Chain from coiling

among the Wheels

Fix the Round Hook into the fusee

Wind up the Watch, be careful the Chain goes

into the Worm of the fusee, N.B. keep

your hand on the Contrate Wheel

let the Watch go down but at times toutch

the Contrate Wheel to prevent too great

velocity

Skrew on the Regulating plate of the Ballance

put on the Ballance & fasten the Spring

then the Plate of the Ballance

then the Minute Wheel

then the Hour Wheel

put in the Pins that fasten the Dial Plate

put on the Hands

Day One: Maps and Plans

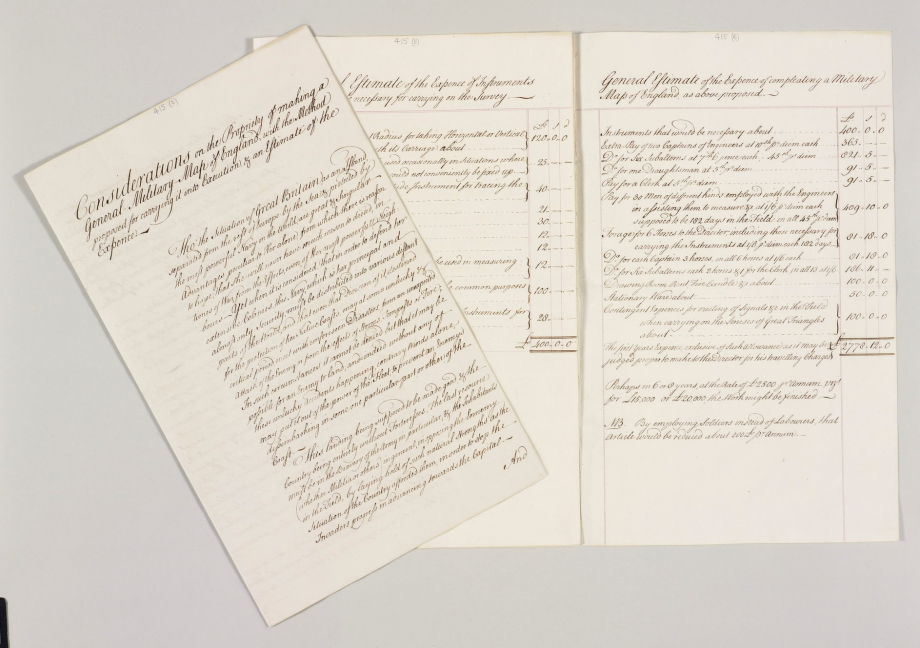

Over the centuries, pioneers in the arts and sciences often demonstrated their new findings or inventions to their Monarch, in the hope of gaining the ultimate stamp of approval. Our first document was thought to have been sent to King George III by General William Roy, outlining the origins of what we now know as the Ordnance Survey.

In the mid-1700s, General Roy trained as a 'Practitioner Engineer' and was particularly skilled in map-making. Whilst serving overseas, he realised that Britain was vulnerable to invasion, and in 1763 proposed that a national survey should be undertaken to facilitate national defence. The proposal was initially dropped on account of the estimated cost.

In 1766, Roy suggested a more modest version of his original proposal, though it was not until the 1780s that he was fully able to undertake work on this national survey. Roy had an illustrious career as a cartographer, eventually reaching the rank of Major-General in the Army and is widely regarded as the founder of the Ordnance Survey.

General William Roy’s memorandum on ‘Considerations on the Propriety of making a General Military Map of England, with the Method proposed for carrying it into Execution, & an Estimate of the Expence’, 24 May 1766 also shows the estimated cost of the equipment that would be necessary to carry out the survey, as well as those required to complete a military map of England.

This document is part of The Georgian Papers Online collection.

Copyright information:

All archive items: The Royal Archives / © His Majesty King Charles III 2022