The Normans came to govern England following one of the most famous battles in English history: the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Four Norman kings presided over a period of great change and development for the country.

The Domesday Book, a great record of English land-holding, was published; the forests were extended; the Exchequer was founded; and a start was made on the Tower of London.

In religious affairs, the Gregorian reform movement gathered pace and forced concessions, while the machinery of government developed to support the country while Henry was fighting abroad.

Meanwhile, the social landscape altered dramatically, as the Norman aristocracy came to prominence. Many of the nobles struggled to keep a hold on their interests in both Normandy and England, as divided rule meant the threat of conflict.

This was the case when William the Conqueror died. His eldest son, Robert, became Duke of Normandy, while the second surviving, William, became king of England. Their youngest brother Henry would become king on William II's death. The uneasy divide continued until Henry captured and imprisoned his eldest brother.

The question of the succession continued to weigh heavily over the remainder of the period. Henry's two sons died young, and his daughter Matilda, whom he named his heir, was denied the throne by her cousin, Henry's nephew, Stephen.

There then followed a period of civil war. Matilda married Geoffrey Count of Anjou, who took control of Normandy. The duchy was therefore separated from England once again.

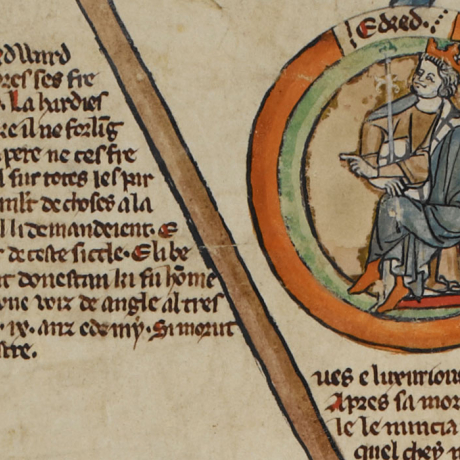

A compromise was eventually reached whereby the son of Matilda and Geoffrey would be heir to the English crown, while Stephen's son would inherit his baronial lands.

It meant that in 1154 Henry II would ascend to the throne as the first undisputed king in over 100 years - evidence of the dynastic uncertainty of the Norman period.